Antiquity;

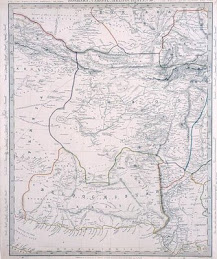

The history of the country of Balochistan, before the march of Alexander the Great through its two provinces, Las and Makuran, was involved in the greatest obscurity. It was presumed that Baluchistan may very probably had been among the one hundred and twenty seven provinces over which the King Ahsuerus, as mentioned in the sacred writings, ruled, from India even unto Ethiopia.

Arrian’s account of the Macedonian monarch’s march from India, through the country of the Oritae and the Gedrosii, clearly shows the former to had comprised the present district of Kolwah, with the tract adjacent to it on the west in the Makuran province, has contributed in some degree to invest these poor and wretched places with no small interest and renown.

Alexander, said to had left Pattala, in Sindh (presumed to be Tatta, on the Indus), some time either in the months of march or April, and to had proceeded in the direction of Bela, crossing in his route the lower ranges of the Brahuik mountains. From there he marched in the direction of Jau, in Makuran, facing a very difficult pass some distance south coast of the ancient town of Gwajak, and here it was that the natives of the county had assembled in considerable numbers to oppose his progress.

He was then supposed to have kept somewhat nearer the coast, crossing the present Kolwah district, where mentioned of the difficulty experienced in procuring water.

The great conqueror’s Admiral, Nearchus, about the same time, under the direction of Alexander and for proposes principally of discovery, coasted along the shores of Baluchistan, and his account of the natives he met with, and the difficulty he found in obtaining supplies, is as credible as if the voyage had been carried on under similar circumstances at the present day.

The severest privations of fatigue, hunger, and thirst had to be endured by all, from the highest to the lowest, and both the fleet and army suffered extreme hardship, until the latter reached the fertile and cultivated valley on the western border of Gedrosia, the present Bumpur; from there it passed into Karmania, now know as the Persia province of Kerman.

It would appear that another detachment of the Greek army marched from India to Persia by a higher route, through Arachosia and Drangiana, the modern Kandahr and Sistan districts. This was the forces under Kraterus, which did not seem to have met with so many difficulties and obstruction as that immediately under Alexander’s command in the country of Gedrosia.

The territory occupied by the Oritae, as mentioned by Arrian’s, would no doubt include the present district of Kolwa and the tract adjacent to it on west. Sixty days after leaving the country of the Oritae, Alexander was reported to have reached Pura, the capital city of Gedrosii. This name, unchanged even at the present day belongs to a town near Bumpur, between Aibi and Kalagan, and about 500 miles west from the town of Bela in Las.

From this expedition of Alexander’s down to the commencement of the eight-century of the Christian era, nothing certain seems to be known of the history of any portion of Baluchistan. It is surmised that it was at times intimately connected with the Persian empire, as a dependent province or provinces, though at other periods exercising it presumed, an independence of its own, divided possibly among a number of chiefs of greater or less power and influence.

In A.D 711, or about a thousand years after Alexander’s march through the country, the army sent by the governor of Basreh, Hejaj, under command of the celebrated Arab general, Muhammad Kasim Sakifi, was supposed to have effected the subjugation of Makuran on its route; and from this may no doubt be traced the colonization of much of country by various tribe of Arab. Between this period and early part of the eleventh century little seems to be known of any part of Baluchistan; but about A.D 1030 it is recorded that Musaud, the son of Mahmud of Ghazni, extended his conquests up to Makuran, but did not penetrate into the mountainous portion of Baluchistan.

His inroad seems to have been confined almost entirely to the level districts, and without ant attempt at a permanent retention of the country. Nor can this be wondered at, since neither the country nor its people were able to offer sufficient inducements for their conquest, though it would seem to be ascertained fact that its wilds and fastnesses were often resorted to by defeated or disappointed competitors for the thrones of neighboring states as places of temporary refuge.

After this there is another great gap in the history of Baluchistan, and nothing at all definite is known till the period of the Brahui conquest, under the direction of Kambar, a chief of the Mirwari tribe, which is believe to have occurred towards the latter end of the seventeenth century.

Before this period there is a tradition that a Muhammadan family, the Sehrais, ruled at Kalat, and their burial ground, says Mason is still shown immediately south of the town walls of the capital of Baluchistan. This reigning family seems to have been displaced by a Hindu caste, the Sewahs, but when they began to wield supreme power in the country, and how long their rule lasted, history does not record.

This much, however, is known, that the Sewahs in their turn were ousted by the Brahui tribe, under the leader already mentioned, and Pottinger thus related the story of the revolution; Kalat had previously been governed by a Hindu dynasty for many centuries, and the last Rajah was either named Sewah, or that had always been the hereditary title assumed by the prince of his race on mounting the Gadi.

This last surmised seems to be the best founded, because the city of Kalat was at that period very frequently spoken of as Kalati Sewah, an appellation it is more likely to have derived from a line of governors than from one individual, unless as was the case with Nasir khan, he was distinguished for great talent and virtues.

Sewah himself resided principally at Kalat, while his only son Sangin, officiated in the capacity of a Naib, or lieutenant governor, at Zehri, in Jhalawan.

The administration of both these princes is allowed to have been very equitable, and to have afforded every possible encouragement to merchants or sojourners in their territories. Sewah was at length obliged to invite to his aid the mountain shepherds their leader, against the encroachments of a horde of depredators from the west part of Multan, Shikarpur, and upper Sindh, who headed by an afghan chief, with a few of his followers and a Rind baluch tribes, infested the whole country, and had even threatened to attack the seat of government, which was nothing better than a straggling village.

The chief who obeyed the summons was Kambar and he was considered to be the lineal descendant of a famous Pir, or saint, who had worked miracle in his time. This gave Kambar and his adherents a weight and respectability among their countrymen, which would have been due neither to the numbers of the latter nor to the hereditary possession of the former, whose paternal property was very trifling indeed, and lay in the district of Panjgur, in Makuran.

On their first ascending the lofty mountain of Jhalawan and Sarawan, these auxiliaries were allowed by Sewah a very small pittance, on which they could scarcely support life; but in a few years either extirpated or quelled the robbers against whom they had been called in, and finding themselves and their adherents to only military tribe in the country, and consequently masters of it, Kamber formally deposed the Rajah, and assuming the government himself, forced number of the Hindus to become Musalman, and under the cloak of religious zeal, put other to death.

Sewah, the Raja, with a trifling portion of the population, fled toward Zehri, where his son Sangin was still in power; but their new enemies daily acquired fresh strength by the enrolment of other tribes under their banners, and at length succeeded in driving them from that retreat, whence they repaired to the cities of Shikarpur, Bkhar, and Multan, and obtained an asylum among the inhabitants there, who were principally of their own creed.

Sewah was said to have died during the latter part of this rebellion, and his son Sangin, being made a prisoner, abjured his faith and embraced Islam, which example was adopted by a good number of his followers, who still retain evidence of their former religion in the name of their tribe, that of Guruwani.

On the accession of Kambar to supreme power, which it was decided by tribes should be hereditary, two counselors, whose dignities also were hereditary, taken from the Raisani and Zehri tribes, were appointed Sardars, the one of Sarawan and the other of Jhalawan. It was arranged, says Mason that these two Sardars, on all occasion of Darbar, or council, were to sit the Sardar of Sarawan to the right, and the Sardar of Jhalawan to the left, of the khan.

From the history files by M.Sarjov

Wednesday, January 20, 2010

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment