| Marine Corps Intelligence Activity Cultural Intelligence for Military Operations: Iran Baluch in Iran |

(U) Cultural Narratives and Symbolic Eras

Schwarz Kathryn(U) Origins of Greatness: Mir Chakar and Nasir Khan

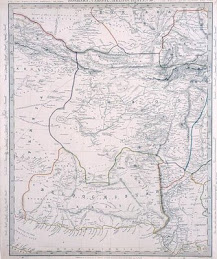

This section explains the significance of Nasir Khan and Kalat, an independent Baluch state in the 18th century.(U) Baluchi nationalists laud Mir Chakar as the first person to politically unite the entire Baluch community. Mir Chakar reigned from 1487 to 1511 and led a large army of Baluch into the area they still inhabit, eastern Iran, western Pakistan, and southwestern Afghanistan. Once there, he began an invasion on northern India (present-day Pakistan). He served as ruler, but his kingdom was eventually destroyed by a civil war between the Rind and Lashari Baluchi tribes.

(U) Today, Baluch call Mir Chakar the Baluch Attila, remembering his military victories while forgetting his inability to maintain control over all Baluchi tribes. Mir Chakar is remembered through stories, ballads, and poems passed from one generation to another.

|

(U) Nasir Khan ruled over the Baluchi principality of Kalat in the 18th century; his achievement remains a symbol of pride for the Baluch and an example of a unified Baluchi political identity. He created a modern administration and established an army of 25,000 men and 1,000 camels. He formed a bureaucracy and delegated tasks to ministers and two bodies of legislature, one made up of representatives of the different tribes and one consisting of elders serving as government advisers. He built roads, inns, and mosques. For the first time, the Baluch rallied under one man and agreed on one system. This dynasty collapsed soon after Nasir Khan’s death in the early 19th century.

|

(U) The reign of Nasir Khan reminds modern Baluch that the Baluch can be powerful, and that foreign interference is dangerous. Iranian Baluch do not seek unification or a confederation of tribes like their fellow Baluch in Pakistan, but they do wish to gain greater autonomy within Iran.

Patriotic Baluchi Song (U) Most Baluchi nationalists in Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan still argue that Nasir Khan could have continued his reign over Baluchistan had the United Kingdom not intervened in the late 19th century. The British played off rivalries between tribal chiefs and divided the once-unified land into seven different parts. One quarter of the area in the west was given to Persia; in the north, a small area of land became part of Afghanistan; the rest was annexed into British India, to the area of present-day Pakistan.

Schwarz Kathryn (U) Pahlavi Dynasty (1921 to 1979): Time of Oppression

This section describes the interaction between the Baluch tribe and Reza Shah and his son, Reza Shah Pahlavi.(U) The Baluch blame the Pahlavi Shahs, Reza and Muhammed Reza, for suppressing their culture. Due to their fear of Baluchi nationalism in neighboring countries and their desire to spread the central government’s authority over all tribal nomads, both Shahs targeted the Baluch. They successfully diminished their power, altered traditional political and economic frameworks, and ended most movements toward an independent Baluchi state.

Reza Shah (U) The Baluch felt particularly damaged by the government's attempts to curb raiding and smuggling. Historically, the Baluch relied on raiding, thieving, and smuggling goods from traveling caravans and nearby cities in eastern Iran and western Pakistan as their primary source of income. This was complemented by animal husbandry and subsistence farming. The items they acquired were sold in legal and illegal markets throughout their territory and sometimes to Persian markets in the north through middlemen.

(U) The Baluch gained a reputation of being fierce, violent, and cunning; their raiding also left them wealthier than many of the other nomadic tribes in Iran. In the 1930s, Reza Shah initiated a series of laws that suppressed the raiding with military might. These laws limited the income of the Baluch and left them searching for a new way to earn money.

(U) The Baluch lived in poverty throughout the 1940s before they found a viable solution. The government worked with Baluchi sardars (chiefs) who served as liaisons between the tribe and the government to provide limited assistance for the tribe. The government provided some aid, such as one irrigation pump for hundreds of Baluch. More than alleviate hunger and poverty, though, the tribes felt that this aid only increased their dependency on the government. The Shah tried to sway the sardars to become his clients, which would lead to more government influence in the tribes. Because the government’s aid was channeled through the sardars, they gained more power within the tribe.

|

(U) The changes imposed by Muhammed Reza Shah were initially devastating, but the Baluch eventually recovered through agriculture and entrepreneurship. They increased date cultivation, providing food and nourishment to their own tribe while also selling and bartering the fruit. The increased investment in date farming caused some Baluch to remain in the Hamuni Mashkil to oversee the dates year-round. These Baluch who settled in one area forfeited their tribe’s traditional migration, social life, and political structure for this new economic endeavor.

Muhammed Reza Pahlavi (U) Individual Baluch also explored entrepreneurship, opening small businesses with capital generated from date profits. One well-known business that began in the 1950s was a taxi service using old Russian motorcycles to carry fellow Baluch and other nomadic tribespeople from one area to another more quickly than any camel could. This business evolved into a human smuggling outfit during the Khomeini revolution, when wealthy Persians sought out the motorcycle-owning Baluchi businessmen, who could help them escape the purges in Iran during the 1980s. The Baluchi dressed the Persians in their traditional robes and, on the back of their motorcycles, transported them out of Iran to safety.

(U) The government limited Baluchi political capabilities by changing political districts and encouraging Persians to migrate to the Baluch’s ancestral land. Reza Shah created the province of Sistan-Baluchistan by lumping together the Baluch and the Sistanis, an ethnic group closely associated with Persians and, therefore, friendlier to the government. He did this to prevent the Baluch from gaining political strength and challenging his leadership. The mixture of the two groups in the new province left the Baluch in the minority and limited their potential political voice. This policy of dividing and diluting the Baluch was reinforced by a systematic immigration of Persian settlers who moved onto Baluchi land and confiscated Baluchi businesses. During this resettlement, 150,000 Baluch migrated from Iran to the Arabian Gulf.

(U) When Muhammed Reza Pahlavi began his rule in 1941, the Baluch were largely subdued, yet the threat of Baluchi nationalism in Pakistan moved him to increase the government’s repressive policies. He aimed to stifle any expression of Baluchi identity. He sought to limit intellectual growth by limiting educational opportunities for younger Baluch, banning the Baluchi language from the few schools Baluch attended, and making Persian mandatory.

(U) Publishing, distributing, or even owning a book, magazine, or newspaper in Baluchi became a criminal offense. He forced Baluchi students to use history books that falsely taught that the Baluch were ethnically Persian. Students were not allowed to wear traditional clothing to school and were seriously reprimanded if they did. Many of these repressive policies continue today.

|

(U) Reza Shah Pahlavi remained afraid of a Baluchi uprising in Pakistan and Iran. The Baluch in surrounding countries, including those who migrated to the Middle East, supported the creation of an independent, united Baluchistan by creating the Baluchi Liberation Front, broadcasting Baluchi separatist news throughout the region, and sending weapons to support the movement within the designated area. In the early 1970s, Muhammed Reza Shah increased his attention to neighboring Pakistan and prepared for the possible disintegration of Pakistan. He feared that the Baluch in Pakistan would overthrow the government then assist Iranian Baluch in gaining power in Iran.

(U) To prepare for this situation, the Shah wanted to have the ability to overtake Pakistan and, therefore, avoid a crisis similar to the one then raging in Vietnam. To make his military ready for this possibility, a joint 2 week field training exercise between Iranian and U.S. Special Forces units near Chah Bahar was held in March 1978. The Iranian forces employed 15 Baluch to serve as their interpreters (for their local language, not English), cooks, and guides. The U.S. forces were surprised at how nervous the Baluchi guides were and how they were excluded from high-level training sessions. The Iranians wanted to train the national military to take over a faltering government. But the Iranian soldiers wanted to keep this information from the Baluch to avoid giving Baluch the capability to take over the Iranian government. After this exercise, the Iranian military began to build bases, roads, and administrative offices in Sistan-Baluchistan. This inadvertently improved the Baluch standard of living as more resources were dedicated to their province.

1970s oil boom created opportunities (U) Increased military activity around their homeland improved their economic standing while the oil boom of the 1970s increased educational opportunities for all Iranians. Yet growing unemployment among the educated Baluch and constant discontent with the government created a surge in Baluchi nationalism. The increase in international oil prices also helped the government assist in areas previously undeveloped. Sistan-Baluchistan was one such area.

(U) Although the numbers were still small compared to Persians—in the Zaheden Teacher Training College only 6 out of 16 graduating students were Baluch—and despite consistent prejudice against them, education among the Baluch was growing. But discrimination outside of the education system was even worse than inside, and few educated Baluch found jobs. The educated, unemployed Baluch had nowhere to go and nothing to do, so many turned to the idea of Baluchi independence.

|

(U) Khomeini Revolution: Nationalism Goes Underground

This section describes the Baluch movement for an independent, autonomous Baluchstan during the radical Khomeini Revolution.(U) The Baluch believed that the 1979 Revolution could serve as the opportunity to alter their relationship with the government and improve their poor status within Iran. They approached Ayatollah Khomeini, with optimism. The collapse of the Pahlavi regime spurred the disintegration of almost all central authority in Iran and the Baluch hoped to gain some autonomy during this political vacuum. Yet Khomeini took a hard-line Shi’a approach to politics, and the Baluchi feared that their Sunni religion might cause problems and exclude them from any gains.

(U) In 1978, the Baluchi Sunni clerics requested a meeting with Khomeini—they believed that, despite their different Islamic beliefs, they were all clerics, therefore they could communicate easily. The meeting took place after Khomeini assumed power; Abdol Aziz Mollazadeh, the principal moulavi (Muslim divine) of the Iranian Baluch, traveled to Tehran to meet with the new leader. Khomeini said what Mollazadeh wanted to hear, that he would respect their religion, treat them equally, and end the discriminatory social practices if the Baluch would support him. Mollazadeh was elated by this conversation and returned to Sistan-Baluchistan to spread the good news.

Ruhollah Khomeini (U) It soon became evident that Khomeini had no intention of keeping his promise to the Baluch; he only supported them after they raised a threat of violence. When the new constitution was drafted in 1979, Shi’a Islam became the state religion. The Baluchi language was still banned in schools. The only concession Khomeini seemed to grant was permission to print newspapers and magazines in Baluchi.

(U) The possibility of any meaningful regional autonomy finally ended with Article 100 of the new constitution. Advisory councils, appointed by the national government rather than elected by the local community, were to oversee the Baluchi tribes. The Baluch felt betrayed after Khomeini’s initial pledge of support, and Mollazadeh voiced his disappointment.

(U) Khomeini’s betrayal sparked Baluchi protests that forced Khomeini to reconsider the Baluch. Armed clashes and loud demonstrations erupted in Sistan-Baluchistan. Two hundred Baluch boycotted the national referendum on the new constitution, set fire to ballot boxes, and held a government official hostage for 3 days before Mollazadeh pleaded for his release. The government unleashed their military on the Baluch, and 24 were killed and more than 80 wounded in the following weeks.

|

(U) Khomeini, startled by the violent Baluchi reaction, reached out to them and sought a compromise: he would create an amendment specifically empowering Sunni minorities to operate their own court systems, despite Shi'ism being the official state religion. Mollazadeh accepted the token concession. Yet many Baluch were unsatisfied and wanted more protection for their language and culture. Whatever unity the Baluch had achieved protesting Khomeini was now gone as disputes within the tribes prevented them from working together.

(U) In the years following the Islamic Revolution, the Baluch’s standard of living remained low due to government neglect of their impoverished region. The Baluch believe that because they are Sunni, have the capability of gaining political strength, and have always worked toward some level of independence, the government refuses to develop Sistan-Baluchistan. Whereas education levels have risen elsewhere in the country, the schools available to the Baluch remain underfunded, and Persian teachers refuse to teach Baluchi language and history.

(U) The Baluchi economy is limited, due to discrimination in hiring practices for both private and public opportunities; many educated Baluch leave the country in search of work. Those educated, unemployed who remain in Iran often direct their energy toward the independence movement.

Schwarz Kathryn (U) Baluch Today: Migration, Division, and Stagnancy

This section explains where the Baluch are today geographically, culturally, and vocationally.(U) Today, Baluch live throughout West Asia and the Middle East, and their attitudes regarding their homeland vary greatly. Because of the limited opportunities within Iran for educated Baluch, most leave the country for Arab states in the Middle East to search for economic advancement and to escape the limitations of discrimination. Uneducated Baluch also leave Iran, to work as unskilled labor in construction projects.

Baluch mother and child (U) Baluch abroad have an acute sense of identity and speak proudly of their heritage though ties to home decrease the longer they live abroad. Some believe that an independent Baluchistan is possible, while many Baluch admit that pursuing independence today is futile. Almost all agree, however, that maintaining their religion and their language is paramount, these are the two characteristics that set them apart from the rest of the world.

(U) Within Iran, there is little hope that their political and social status will change within the current conservative religious structure of the government. Most Baluch have accepted their nomadic lifestyle and appreciate the freedom inherent in it while acknowledging its limitations. Most Baluch do not expect significant change in their condition without drastic change in Tehran. Those Baluch who voice their dissatisfaction and work for equality are the vocal minority. They are the educated unemployed who participate in the national political discourse and refuse to give up the idea of independence.

|

| (U) Traditional Women's Dress |

1 comment:

thanks for informative site. please send me your email. i would like to contact you. my email address is:

balochforunity@gmail.com

waiting for your reply.

thanks.

baloch for unity

Post a Comment