A GLIMPSE ON THE

BALOCH NATIONALIM

By Professor Dr.

Taj Mohammad Breseeg

The

20th century has been witness to the rise and

development, of the politics of Baloch identity and nationalism.

Nationalism may be defined in one of two ways – by ethnic or

civic criteria. While ethnic nationalism is based on the

consciousness of a shared identity, culture, belief in common

ancestors and history, civic nationalism is encompassed within a

geographically defined territory. In practice, ethnic

nationalism has had an advantage over territorial or civic

nationalism because the former appears as a natural continuation

of a pre-existing ethnicity. The nationalists believe that their

corporate interests are best protected by possession of their

own state in the international system.

A

community has an identity when its members are able not only to

distinguish it from other communities, but also to convey its

distinctive character in words, gestures, and practices, so as

to reassure them that it should exist and that they have reason

to belong to it. Thus the emergence of a national identity

involves a growing sense among people that they belong naturally

together, that they share common interests, a common history and

a common destiny. To this extent the Baloch have undoubtedly an

obvious claim to national identity, as demonstrated by

perceptible political, economic and social events peculiar to

the Baloch.

Historically,

the period between the 13th century and the end of

the 15th was the most significant in the development

of the Baloch ethno-linguistic community. With respect to this,

the process was just as complex and fundamental. Internally, the

Baloch society moved from the smaller unit of clan to the larger

one of tribe and territorial differentiation. Externally, it

began to assimilate vast segments of other ethnic groups:

Iranians, Indo-Aryans of Punjab and Sindh, Arabs, Pashtuns, etc.

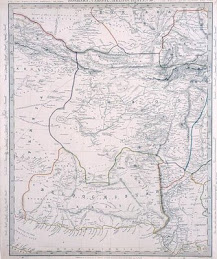

A nation may be divided amongst several states. Such a nation is

a multi-state nation - or, more appropriately, a trans-state

nation. The Baloch today are a trans-state nation. Since the

1920s, their ‘coherence and unity’ have been growing steadily,

and it is directed to the establishment of an independent

“Greater Balochistan”, which

comprises

mainly the Pakistani province of Balochistan, the Iranian

province of Sistan-wa-Balochistan (Sistan and Balochistan), and

the contiguous areas of southern Afghanistan. Thus, as ties of

history, territory and ethnicity maintain a unified Baloch

national identity that spans state frontiers, so does Baloch

nationalism transcend the international boundaries, which cut

across its linguo-ethnic homeland. Therefore, it is important

to place the Baloch national struggle in Eastern Balochistan

(within the state of Pakistan) in the context of the broader

nationalist movement engulfing the Baloch in Iran and

Afghanistan.

Numbering

over 10 million (1981), the Baloch are one of the largest

trans-state nations in southwest Asia. At present, their country

is politically divided into two major parts: eastern Balochistan

with Quetta as its capital has been administered by Pakistan

since 1948; western Balochistan, officially known as

“Sistan-wa-Balochistan” with Zahedan as its capital, has been

under the control of Iran since 1928. The greatest number of

Baloch today still live in Balochistan, though a large Baloch

diaspora has developed in this century, especially in Karachi

and other cities of Sindh, Punjab, Oman, and in recent decades

in the Gulf States as well.

The Baloch people are distinct from the Punjabi and the Persian

elite that dominate Pakistani and Iranian politics - they are

Muslims but more secular in their outlook (in a similar fashion

to the Kurds) with their own distinct language and culture.

However, it is Balochistan’s strategic location, with a long

coastline on the Gulf and its function as one of the gate-ways

from and to Central Asia and Afghanistan, and as the most

important check point of the Gulf’s oil, that has placed it in a

pivotal position in the Subcontinent's, and since the post

colonial years in Pakistan's and Iran’s, history.

Having

its origin in the Balochs’ distinct geography, ecology, culture

and history, Baloch nationalism emerged as an ideology in the

early 1920s. Representing a popular movement against alien

domination, its principal goal is the Baloch national self-rule

in their homeland, an aim sought to preserve their national and

cultural identity, thus advocated and pursued universally by the

Baloch of all classes and social strata.

The

ethnic element (ethnicity) constitutes the salient feature of

Baloch nationalism. The weakness of ethnicity, however, is its

inability to maintain the terminal loyalty of the masses at the

national level. Sub-national rivalry, based on tribal loyalties,

divides the Baloch national movement. These rivalries are then

used by the central governments to weaken the Baloch, in both

Iran and Pakistan. Thus the Baloch movement, in contrast to many

other national liberation movements, has experienced a

persistent contradiction between its traditional leadership and

the relatively developed society it seeks to liberate.

A strong

sense of ethnicity has existed among the Baloch for a very long

time. From the 17th century to the mid-19th century, much of

Balochistan was under the rule of the independent Khanate of

Kalat, and the autonomous Baloch principalities (Western

Balochistan) that produced a flourishing rural and urban life in

the 18th century. Although a people of mixed origin, the Baloch

constitute an ethnicity which has proved its vigour throughout

the ages. They have withstood the inroads of more numerous and

developed peoples such as the Mughals, Turks and Persians, and

despite certain affinities with the latter, they have succeeded

in maintaining their separate identity. Their vitality has been

demonstrated by expansion into non-Baloch regions as well as by

the Balochization of neighbouring people.

The Baloch

may be divided into two major groups. The largest and the most

extensive of these are the Baloch who speak Balochi or any of

its related dialects. This group represents the Baloch “par

excellence”. The second group consists of the various

non-Balochi speaking groups, among them are the Baloch of Sindh

and Punjab and the Brahuis of eastern Balochistan who speak

Sindhi, Seraiki and Brahui respectively. Despite the fact that

the latter group differs linguistically, they believe themselves

to be Baloch, and this belief is not contested by their

Balochi-speaking neighbours. Moreover, many prominent Baloch

leaders have come from this second group. Thus, language plays a

less important role in the Baloch nationalist movement in

Eastern Balochistan, because, as indicated above, language ties

do not unite the whole Baloch community.

Despite the heterogeneous composition of the Baloch, in some

cases attested in traditions preserved by the tribes, they

believe themselves to have a common ancestry. Some scholars have

claimed a Semitic ancestry for the Baloch, a claim which is also

supported by the Baloch genealogy and traditions, and has found

wide acceptance among the Baloch writers. Even though this

belief may not necessarily agree with the facts (which, it

should be pointed out, are very difficult to prove, either way),

it is the concept universally held among members of the group

that matters. In this connection Kurdish nationalism offers a

good parallel. The fact is that there are many common ethnic

factors which have contributed to the formation of the Kurdish

nation; there are also factors which have led to divisions

within the Kurds themselves. While the languages identified as

Kurdish are not the same as the Persian, Arabic, or Turkish,

they are mutually unintelligible. Geographically, the division

between the Kurmanji-speaking areas and the Sorani-speaking

areas correspond with the division between the Sunni and Shiite

schools of Islam. Despite all these factors, the Kurds form one

of the oldest nations in the Middle East. It is interesting to

note that like the Kurdish ruling tribes, various Baloch ruling

tribes have also pretended to an Arab descent and proudly

displayed Arab genealogy – a fact no doubt due to the religious

prestige which attaches to Arab descent among Islamic peoples.

However, even those who have claimed such descent have never

considered themselves anything but Baloch.

The

Balochs’ ethnic background, social organisation, culture,

history, and sense of territoriality are proof of an age-old

Baloch qaum (nation). In many ways, this is a projection

of modern concepts into the past. Nevertheless, the Baloch have

undeniably had a pool of characteristics which encouraged the

development of separate identity well before the 20th

century and gave rise to an assertive ideology of Baloch

nationalism during the national movements of 1920s and onward.

Thus they are united by their belief in common ancestors,

culture, history and Sunni Islam. While there is no one dialect

or language common to all Baloches, the speakers of the various

dialects and languages regard themselves as Baloch and are so

regarded by one another. A unity of tradition and culture

complements this unity of languages. While it is true that

Baloch are divided today between tribesmen (migratory or

sedentary) and urban dwellers, their social mores were formed in

the tribal cauldron.

Of the

various elements that go into the making of the Baloch national

identity, probably the most important is a common social and

economic organisation. For while many racial strains have

contributed to the making of the Baloch people, and while there

are varying degrees of differences in language and dialect among

the various groups, a particular type of social and economic

organisation, comprising what has been described as a “tribal

culture”, is common to them all. This particular tribal culture

is the product of environment, geographical, and historical

forces, which have combined to shape the general configuration

of Baloch life and institutions.

The

above-mentioned characteristics of the Baloch not only unite

them but also separate them from the dominant neighbouring

cultures. This recognition of their ethnic separateness is

reinforced by the separation of the Baloch from the Pakistani

and Iranian national economies. Whether this non-participation

is based on the difference between centre and periphery, urban

vs. rural, industry vs. agriculture, or intentional

discrimination, Balochistan lacks modern factories and modern

industries. It has shared in neither the development of these

countries’ infrastructure nor in the rewards of their economic

development.

The Baloch

history, tradition, culture, language, sense of territoriality

and their common ethnic background form the cohesive bases of

Baloch nationalism, while geography has had both positive and

negative effects on it. Geographical isolation, of course, did

not give rise to nationalism, but there are few factors that

strengthen the nationalism of a people more that the belief that

they are culturally and historically unique in the world. To the

extent that geography was responsible for the uniqueness of the

Baloch character, culture, and history, it helped create a

national particularism, which in turn served as a catalytic

force for the growth of national sentiment in Balochistan.

The same

climatic and geographical conditions that aided the growth of

Baloch nationalism, from another point of view hindered this

growth. As the difficult mountain and desert terrain

historically protected their independence, and made it difficult

for invaders to annex the Baloch territory, on the other hand,

the harsh climate and scarcity of water did not give the Baloch

a chance to emerge as a feudal nation. The harsh climate and the

scarcity of water forced the Baloch to live a nomadic or

semi-nomadic life or to migrate to the Indian subcontinent,

Central Asia, East Africa, or the Arab Middle East.

Balochistan can boast vast gas deposits as well as minerals like

chromium, copper, iron and coal. Gas is found in commercially

viable quantities in Sui and Pirkoh (Pakistan). This is an

important factor in the attitudes of the various Central

governments regarding the question of Baloch self-determination,

and has strengthened the Balochs’ own feeling of being treated

unfairly.

The

historical experiences have played an important role to the

formation of the Baloch national identity. In this connection

the Swiss experience shows a remarkable similarity. In the Swiss

case strength of common historical experience and a common

consensus of aspirations have been sufficient to weld into

nationhood groups without a common linguistic or cultural

background. It should be remembered that the history of the

Baloch people over the past hundred years has been a history of

evolution, from traditional society to a more modern one. (“More

modern” is a comparative term, and does not imply a “modern”

society, i.e. a culminating end-point to the evolution.) As

such, the reliance on tribal criteria is stronger in the earlier

movements, and the reliance on nationalism stronger in the later

ones. Similarly, the organizing elements in the early movements

are the tribes; the political parties gradually replace the

tribes as mass mobilisation is channelled into political

institutions.

The

Baloch constitute a nation distinct from that of the Persians

and Punjabis by every fundamental test of nationhood, firstly

that of a separate historical past in the region at least as

ancient as that of their neighbours, secondly by the fact of

their being a cultural and linguistic entity entirely different

from that of the Persians and Punjabis, with an unsurpassed

classical heritage and a developed language which makes Baloch

fully adequate for all present-day needs and finally by reason

of their territorial habitation of definite areas.

The

growing presence and power of the British East India Company

along the coastal and eastern provinces of India and the

simultaneous disintegration of the Mughal Uzbek and Safavid

empires in India, Central Asia, and Persia respectively, ripened

the conditions for the whole of Balochistan to unite within the

framework of a single feudal state (Kalat State). The rulers of

the mightiest of the khanate accomplished this unification. They

came from the Kambarani or Ahmadzai dynasty (from the founder of

the dynasty-Mir Ahmad who reigned in 1666-1695). However, it was

the sixth Khan of this dynasty, Nasir Khan I, known as the

Great, who drove the frontiers of the Khanate of Kalat northward

into Afghanistan, southward into the Makkoran, westward deep

into Persian territory, and eastward into Punjab and Sindh as

far as Karachi.

The Baloch

destinies, however, changed radically around the time, when the

British and the Persians divided Balochistan into spheres of

influence, agreeing on a border in the mid-19th

century. It should be remembered, up to the British advent, the

Baloch had developed into a major power in the region. They were

ruling not only Balochistan, but also the two richest provinces

of the region, Sindh and Sistan. The British, whose occupation

of the eastern part of Balochistan began in the 1840s, were

interested in Balochistan for military and geopolitical reasons.

In order to protect their colony (India) from the rival

expansionist powers such as Russia, France, and Germany, the

British used Balochistan as a base to protect their interests in

their sphere of influence (Afghanistan and the Persian Gulf

region).

To prevent

Baloch unity and to suppress their nationalist tendencies the

British exploited the Baloch tribal system. Sir Robert Sandeman

advocated a new socio-political system, called the "Sandeman

System" or Sardari Nizam for developing the authority of

the tribal chiefs. In 1854, the Khan of Kalat became a British

protectorate. The treaty of 1876 gave birth to new political

forces in Baloch society, the decline of the powerful feudal

overlord (the Khan) and the rise of a new feudal elite (Sardars).

The Sandeman system granted complete autonomy to the tribal

areas. The status of the Sardar (chief among equals) was

changed into that of a feudal lord and the tribesmen were

declared subjects.

The spread of

the modern doctrines of nationalism among the Baloch, and the

resulting active participation of the Baloch intellectuals in

nationalist activities was in large measure a reaction against

British and Persian supremacy. The First World War and its

aftermath mark an important stage in the growth of Baloch

nationalism. The extent and intensity of nationalist feeling

among the Baloch was profoundly influenced by the impact of the

Russian Revolution, the defeat and break-up of the Ottoman and

the abolition of the Caliphate, the anti-imperialist movements

of the Afghans and the Indians, and the revolutionary ideas set

in motion by these events, as well as by the propagation of the

Wilsonian principles of national self-determination.

Frequent internal

divisions of tribe and social class have marked the development

of Baloch nationalism since its emergence in the 1920s. National

boundaries have also fragmented Baloch nationalist groups and

made it difficult to present a united front to governments.

Governments too have become adept at exploiting Baloch

divisions. Their policies towards Baloch minorities have often

shaped the goals of Baloch nationalist parties - which at

various times have called for cultural and social rights,

autonomy or independence.

The

first apostle of the Baloch national movement was Yusuf Ali

Magasi. In the early 1920s, Magasi and his friends established

the “Anjuman-e Ittehad Balochan” (Organization for the Unity of

Baloch), an underground political organization, for the

liberation of Balochistan. From 1931, the Anjuman with Magasi as

its president started to work openly. Having lived in his youth

in cosmopolitan Lahore (British India), Magasi was familiar with

the anti-imperialist struggle and the material advancement of

modern nations. Magasi’s definition of Baloch nationalism, and

his understanding of who was a Baloch, was based on history,

tradition, bloodline and religion.

Thus

the material with which the early Baloch nationalist leaders

began to build Baloch nationalism was the ethnic characteristics

of the people of Balochistan and the surrounding area. As

discussed in chapter three, the Baloch have a long history,

going back to at least 3000 years. They have creation myths, a

written record, and a body of literary works (primarily oral).

While the Persian and the Punjabi peoples share many of these

earliest cultural markers, there are sufficient differences to

mark the Baloch as a unique people. Being a colonial movement,

the Baloch national movement picked up the language of European

nationalism as early as the 1920s. Thus, concepts such as the

modern nation, identified homeland, and the right of

self-determination, were taken from European ethnic movements.

The Baloch have

consistently resisted all attempts at encroachment upon their

independent status, whether by the British or the Iranian

governments. Their various rebellions in the Eastern and Western

Balochistan, besides being violent manifestations of Baloch

nationalist sentiments, were also waged in defence of the Baloch

way of life. The extension of the external authority of the

British into the Baloch country, accompanied by the new and

unfamiliar economic and technological process of modern

civilization, roused the tribal resistance in the same manner

that it had roused the resistance of the Pashtun tribes in the

mid-19th century, and increased the vehemence of

Baloch nationalism.

It appears

that the British reversed their policy in respect to Balochistan

after the advent of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia in 1917.

Thereafter, concerned with containing the spread of the October

Revolution, they assisted Iran to incorporate western

Balochistan in 1928 in order to strengthen the latter country as

a barrier to Soviet expansion southward. The same concern also

led later to the annexation of Eastern Balochistan to Pakistan

in 1948. Henceforth, the Baloch and their homeland were divided

against their will between three states, in order to enable one

great power to enhance its strategic position against another

big power.

Thus, as

indicated above, the superimposed division, in turn, has

provoked the rise of Baloch nationalism and their sense of

irredentism, bringing them into conflict with their respective

states, which are intent on preserving the inherited status quo

from the big powers. It is the superimposition of this division

that has served as the main cause of conflict between the Baloch

and the states in which they were incorporated. Since then, the

Baloch nation, with its distinctive society and culture has had

to confront in both of the “host” states centralizing,

ethnically-based nationalist regimes – the Persians and the

Punjabis – with little or no tolerance for expressions of

national autonomy within their borders.

Following the fall of Mir Dost Mohammad Khan in western

Balochistan in 1928, the aggressiveness of nascent Persian

nationalism gave rise to new grievances and apprehensions, for

besides wounding Baloch national pride; it threatened the Baloch

national identity with extinction. The Pahlavi regime was intent

on building a Western-type secular nation – based on the Persian

national, linguistic and cultural identity. The Baloch response

was a series of revolts throughout the 1930s, led by the tribal

chiefs. However, by the end of 1937, the last of these was

brutally repressed. Thousands of Baloch migrated to eastern

Balochistan and Sindh. It should be noted that, while some of

these revolts were well organised and had well-defined political

aims, others were no more than violent protest against some real

or imagined injustice. Whatever their cause, every fresh

outbreak seemed to fill the cup of Baloch bitterness.

Obviously one of the main reasons for the failure of the early

Baloch revolts was the local, feudal, tribal and patriarchal

characteristics of revolts, which often centred around a local

influential leader, followed by the members of his tribe. Even

the Baranzais in Iranian Balochistan, although well organised at

the higher levels, never penetrated to the broad masses of the

Baloch people. Similarly the major cause of the failure of the

1930s and the 1940s national movements was the lack of a modern

social basis for nation building. The Sardars opposed

modern institutions and reforms. From 1929-1948 there were no

colleges, universities or industries. There existed only the

tribal elite and the oppressed class of nomads and peasants. The

nationalists, mostly of lower middle-class background, were not

in a position to mobilise the Baloch people in the tribal areas

because of the strong control of the chiefs as well as the

opposition of the British. To weaken the tribal chiefs they

looked for help outside the border of Balochistan. They entered

into an alliance with the All India Congress (while the Muslim

League refused support because of its alliance with the Khan and

the Sardars).

In the twentieth century

the formation of new nation-states following World War I and the

partition of the Indian sub-continent in 1947, had a profound

impact on Baloch society. Since then, Baloch history has been

dominated by struggles between communities, which became

minorities in new nation-states and national governments which

have sought to divide, to dominate and to suppress their

aspirations. These conflicts have created large population

movements. Many thousands have been forced to leave their homes

and land and many more migrated to escape poverty and

oppression. As discussed in chapter two, the Baloch regions of

Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan have remained among the least

developed in those countries. Tribal ties remain strong in many

areas, and tribal leaders are still influential at local level,

especially in Eastern Balochistan (Pakistan). However,

population movements to the cities and the process of

urbanization in recent decades have created new forms of

political and social organization.

In

1947, the nationalists faced a new situation in the politics of

Balochistan due to the lapse of paramountcy. It is important to

note that the disintegration of the British Empire gave the

Baloch an opportunity to regain their freedom from the British.

Following the end of the War, intense political activities

developed among the Baloch nationalists in Balochistan. They

obtained a parliamentary majority in the elections of 1947. In

1948, while the nationalists were struggling for independence,

the Sardars, made an alliance with the Muslim League. In

return, Jinnah promised to look after their interests. The

reactionary tribal elite could not join the Khan who wanted to

introduce modern institutions instead of protecting the tribal

and feudal system. Thus, the annexation of Balochistan into

Pakistan was a result of the old and dying tribal and feudal

system, represented by the Baloch tribal chiefs. The Anjuman

(1920-1933), and the Kalat State National Party (1937-1948)

represented the Baloch masses opposed the Sardary System.

In March

1948, contrary to the agreement of August 1947, Pakistan

forcefully annexed the Khanate of Kalat. Thus, the Baloch state,

which emerged with the first Baloch confederacy under Mir Jalal

Han in 12th century, came to a tragic end in 1948,

one year after the partition of the Indian subcontinent to India

and Pakistan in 1947. For a brief period (1952-55), however, the

Khanate was given semi-autonomous status as the Balochistan

States Union. But this arrangement collapsed when West Pakistan

was declared a single province in October 1955. In July

1970, Balochistan was restored to separate provincial status,

its boundaries incorporating the former British Balochistan and

the Balochistan States Union.

During the

fifty years of the existence of Pakistan, three wars have been

waged in Balochistan. Agha Abdul Karim’s rebellion was the first

in a series of insurrections against the government of Pakistan.

Under the pressure of the Pakistan government, the Khan of Kalat

declared Agha Abdul Karim and the National Party to be rebels,

on May 24, 1948. Because of its resistance to annexation and its

co-operation with the rebel prince, Agha Abdul Karim, the

Government of Pakistan banned the Kalat National Party in June

1948. On May 26, 1948, Agha Abdul Karim with his rebel group had

entered Afghanistan and set up his headquarters at Mazar

Mohammad Karez in the Shorawak area, in the hope of acquiring

support for a sustained war against Pakistan. But the Afghan

Government did not approve of the presence of the prince and the

National Party in its territory.

Agha Abdul

Karim’s resources were limited and so was his area of

operations. Karim started his movement in the Jhalawan area,

backed by some nationalist leaders and with the secret approval

of the Khan. His rebel followers were not more than 500 to 700.

Due to poor planning and the lack of the expected support from

Afghanistan, the prince and his partisans were forced to

re-enter in Pakistan and surrender. Agha Abdul Karim’s rebellion

was clearly of little immediate importance because it lacked

both unified Baloch political support and Afghan military

support. But what did make it significant in the long run was

the widespread Baloch belief that Pakistan had betrayed the safe

conduct agreement. The Baloch regard this as the first of a

series of “broken treaties” which have created an atmosphere of

distrust over relations with Islamabad. Agha Abdul Karim and his

followers were all sentenced to long prison terms and became

rallying symbols for the Baloch nationalist movement.

The 1950s and

1960s were decades of political upheaval in Pakistan. In

Balochistan tribal structures suffered major setbacks, largely

due to detribalisation and the rise of urban population, and

later to land reforms initiated by the central governments.

Similarly, a visible change occurred in the cultural field. In

the early 1950s, the Baloch press was established. In the

subsequent years of the 1960s and the 1970s many books,

periodicals, and newspapers proudly reported the evidence of the

past. Thus to heighten national consciousness, new avenues were

opened to learn about the past, about present culture, and about

other national phenomena by means of written words. Since then,

by the popularisation of Baloch history, Balochi classical

poetry and the positive characterisation of Baloch personality

and society, the Baloch press has played an important role for

the imagination of the Baloch nation.

Following the

fall of the Khanate, the Baloch leadership accepted the

political reality of Pakistan. As for ideology the “Ustaman Gal”

(People’s Party) marked the first time in Baloch history that

the Baloch stopped asking for outright independence. They

couched their demands in terms of autonomy. The Party, however,

maintained that only elected democratic governments at the

provincial and national levels would guarantee autonomy to the

minority nationalities within the framework of constitutional

provisions.

The

continued existence of military rule in Pakistan from 1958 to

the early 1970s obstructed a democratic solution to the

Balochistan problem and exacerbated inter-regional tension. The

prospect of a democratic political system was lost when the

Pakistan army refused to accept the results of Pakistan’s first

general election in 1970, which led to the dismemberment of the

eastern half of the country, now known as Bangladesh. Moreover,

the sense of betrayal by Bhutto’s civilian regime, which had

signed constitutional guarantees of Balochistan’s autonomous

status, added to the growing nationalist sentiment, which

fuelled the four-year rebellion in the 1970s.

Throughout

the period since the partition, Baloch have had an uncomfortable

relationship with the central government of Pakistan: relations

were poorest in 1973 when they engaged three divisions of the

Pakistan armed forces in a bitter and intense armed struggle. In

1973, the Pakistani security agencies discovered Soviet arms in

the Iraqi Embassy at Islamabad. The government alleged that

these arms were for the liberation movement of Balochistan. The

Baloch nationalists not only denied this allegation, but also

regarded it as a conspiracy by Bhutto and his allies to provide

a cause for military intervention aiming at a take-over in the

province.

However,

despite a new constitution, which guaranteed a degree of

provincial autonomy, in less than a year the Prime Minister of

Pakistan, Zulfikar Bhutto, dismissed the Baloch government on 12th

February 1973. In justifying the dismissal, the centre charged

the provincial government with responsibility for several cases

of lawlessness in Balochistan and alleged its support, in

collusion with foreign governments, for Baloch and Pashtun

separatists. In practice, however, Bhutto acted against the NAP

because, having provincial governments led by a party other than

his own, limited his personal authority, and because of the

pressure from the Shah of Iran.

Thus, in the

1970s, open warfare between the Pakistan military and Baloch

nationalist guerrillas, whose demands ranged from self-rule to

outright independence, racked Balochistan. Guerrilla war went on

for more than four years and came to a stand still in 1977, when

General Zia ul-Haq ousted Bhutto. However, the Baloch movement,

which had come into being in the aftermath of Sardar Ataullah

Mengal’s government, might have lost its ardour, but it did not

die, as claimed by the Pakistani authorities. In fact, a case

can be made that national feelings have grown in potential in

the Baloch society and, given the right circumstances, could

mount an even greater challenge to the Pakistani state. Mir

Ghaus Bakhsh Bizenjo’s demand for the specific inclusion of the

right of secession for the federating units in the event of

military take over in violation of the constitution indicated a

deep mistrust of the country’s political set-up by the Baloch in

the 1980s.

Though it is true that Baloch

uprisings in 1948-50, 1958-69, and of 1973-1977 were mostly

fought on the inter-tribal basis, but it would be highly

misleading to term these uprisings just confrontation of some

sardars (tribal chiefs) with central government to safeguard

their narrow feudal interests and privileges as some Pakistani

scholars allege.[1]

On the contrary, these uprisings were very reflection of

growing contradiction between the newly built modern centralised

state of Pakistan and a distinctive national group, the Baloch.

The 1973-77 insurgency intensified the

ever-widening gap of distrust and mistrust between the Baloch

and the central government. This mistrust ultimately gave way to

greater demands for a confederation of the four peoples of

Pakistan. The leaders of the sub-nationalities, in self-imposed

exile, formed an organisation, the Sindhi, Baloch, Pakhtun Front

(the SBPF), in April 1985 in London to demand a confederation in

Pakistan. Similarly, the so-called democracy of the 1990s in

Pakistan like that of its military rule led to further

alienation of the Baloch. Speaking on May 2001, in a PTV

(Pakistan TV) programme on provincial autonomy, the former Chief

Minister of Balochistan, Akhtar Mengal blamed the rulers of

Pakistan for suppressing the will of the Baloch people and

violating flagrantly all the previous accord, including the one

made with the Khan of Kalat on August 4, 1947.[2]

By

contrast, in Iranian Balochistan, Reza Shah and subsequently his

son Mohammad Reza adopted an iron-fist policy towards the

Baloch. For the past several decades the Persians have never

hesitated to use their military might against the Baloch to

silence their voice. The official Iranian policy reflects their

determination to suppress any nationalist movement in their

country. It was due to this background that the Baloch national

movement in Iran was less vocal than its counterpart in Pakistan

in the 1960s and 1970s.

The Iranians

used harsh methods to crush Baloch identity. It was forbidden to

wear the traditional Baloch dress in public or to speak Balochi

in schools, and it was a criminal offence to publish,

distribute, or even possess Balochi language books, magazines,

or newspapers. Balochistan was isolated from the outside world

and closed to foreigners. The Iranian policy of destruction of

the Baloch identity, or Persianization of the Baloch under the

Pahlavis may truly be comparable to that of the Turkish

government’s policy against the Kurds under Kemal Ataturk

(1923-38). The Turkish government followed a policy of

systematic extermination and Turcification of the Kurdish people

in the Turkish controlled Kurdistan. Thousands of Kurds were

deported to Western Anatolia, the Kurdish language was

officially banned and Kurdish books were confiscated and burned.

Even the words “Kurd” and “Kurdistan” were to be omitted from

all textbooks. The Kurds were to be called Turks – “mountain

Turks”. Consequently, this policy of Turcification fanned the

Kurdish nationalism furthermore and deepened their separatist

aspirations. As the Turcification of the Kurds in Turkey

provoked the Kurdish nationalism, so did the Persianization

policy of the Iranian authority to the Baloch nationalism in

Iran.

During the

whole Pahlavi era the Persians continued their assimilation and

Persianization policies in western Balochistan. In 1957-9 and

again in 1969-73, the Pahlavi administration used military force

to crush Baloch resistance to its attempts to enforce

assimilation. Subsequently, more subtle 'pacification' methods

were used. Baloch tribal leaders were appointed as

intermediaries and representatives of government interests with

the aim of bridling the economic and social development of

Sistan-wa-Balochistan. In spite of the application of diverse

means of subjugation, the Iranian Baloch maintained a perception

of themselves as a culturally independent qaum (nation).

This was demonstrated by insurgencies against the Khomeini

regime, which initially raised the hopes of the Baloch for

greater provincial autonomy.

The

Shah of Iran gave much importance to the area, which he always

considered very important for the security of his country. Since

Iran had a Baloch minority problem, any uprising in eastern

Balochistan was thought to directly influence Iran. The Iranian

government under the Shah kept a close watch on developments in

the Pakistani part of Balochistan. Iran and Pakistan

collaborated, due to their joint fear of Baloch national

aspirations. It was argued that one of the reasons Pakistan’s

Prime Minister Z. A. Bhutto dismissed the nationalist government

in the province was because the Iranian government thought the

Baloch nationalists in eastern Balochistan, might encourage

dissidents in western (Iranian) Balochistan.

With

the collapse of the monarchical regime in 1979, the Baloch began

their political activities openly. The “Sazeman Demokratik”, the

“Ittehad ul-Muslimeen”, the “Zrombesh”, and many other political

and cultural organisations were formed in Balochistan. This

period, however, lasted months, not years. The pattern was

repeated of Baloch nationalist aspirations reappearing whenever

the central government showed weakness. The new regime pursued a

policy of Persian ethnic supremacy toward Balochistan, a

continuation of the policies of the monarchy.

By

comparison, however, like the Baloch political parties in

Eastern Balochistan (Pakistan), the major nationalist

organisations, which came into existence during or after the

Iranian revolution, concentrated their demand on self-autonomy

for Balochistan within Iran. However, the Baloch political life

was short-lived in Iran. In the early 1980s, the clerical regime

ordered the Baloch parties disbanded, to be replaced with

Islamic komitehs (committees) and Revolutionary

Guards controlled by the central government. Ayatollah

Khomeini distrusted the Baloch not least because theirs was a

purely secular agenda. Moreover, he was a Shiite Muslim and the

Baloch were predominantly Sunni. While the Baloch could be

acknowledged as Sunnis, no ethnic or “national” minorities were

recognised in the new constitution of the Islamic Republic.

Since the end

of the Second World War great changes have occurred for the

Baloch throughout Balochistan – gradually at first but

accelerating since 1970 because of the changed political economy

of the Persian Gulf. In Afghanistan major factors affecting the

Baloch have been the Helmand river development schemes, the

government’s Pakhtunistan policy, and the Afghan Revolution in

1978. In Iran the successive Pahlavi governments attempted to

neutralise the Sardars and at the same time suppress any

activity among the Baloch that could lead to ethnic

consciousness or solidarity.

Comparatively, the conditions of the Baloch in Pakistan are

definitely better than those of Iran and Afghanistan. But they

are still far from satisfactory, the Baloch of Pakistan have

consistently fought to improve them economically, culturally and

politically. In Pakistan too the Baloch have suffered much

injustice. Consider, for example, what happened to the Baloch in

the 1973-1977 insurgency. Like their brethren in Pakistan, the

Baloch in Iran also consistently resisted the reactionary

Persian domination and have shown a fervent desire to live under

an independent or autonomous Baloch State as their natural

right.

Since

the early 1970s, the growing modern intelligentsia has been

displacing the traditional intelligentsia, mainly the sardars

and the mollas, in the urban centres. In the 1993

elections, the BNM (Balochistan National Movement) a mainly

middle class party, succeeded in winning two national assembly

and six provincial assembly seats. In the provincial elections

of 1993, the BNM secured over 60 percent from Makkoran.[3]

Another feature of changing social relations is the increasing

access of urban women to education, and their participation in

social, economic, political and cultural life outside their

homes. These transformations left their impact on the

nationalistic movement, expanding its social bases and

increasing political, ideological and organizational tension.

Moreover, the circulation of money

during the Bhutto period, and the fruits of the Gulf syndrome

gave strength to the Baloch middle class whose interest collided

with its more powerful and well-established Pashtun counterpart.

As a result, business sectors such as transport, which were

previously monopolised by the Pashtuns, are now witnessing the

entrance of a rising Baloch middle class. The change of

ownership of some transport businesses like Chiltan Transport

from Pashtun to Baloch hands in 1992 was another testimony of

this fact.[4]

Baloch

nationalism is the antithesis to the politically and

economically dominant and exploitative Iranian (Persian) and

Pakistani (Punjabi) states’ nationalism, a pattern similar to

the rise of the Kurdish nationalism in the Middle East (Iran,

Iraq, and Turkey). In spite of more than 70 years of its

existence, Baloch nationalism has not succeeded in achieving its

goal, the right of self-determination for the Baloch nation. It

is difficult to reach a single plausible explanation, but

judging from the finding of this study, one could cautiously

conclude that by that time due to a dominant tribal social base,

a sense of Balochness had not evolved which was sufficiently

strong to force a different course of events.

Nevertheless,

the Baloch nationalism has steadily developed. Every time, after

being crushed, the national movement arose more forcefully than

before. Comparatively, in 1948, Agha Abdul Karim and his rebel

followers were about 500 to 700. In 1958, Nauruz Khan fought in

a wider area against the Pakistani army and around 1000 to 5000

guerrillas were with him. By July 1963, the guerrilla activities

under the command of Sher Mohammad Marri increased in the

Jhalawan and Marri areas. The fighters had established a score

of camps, where the people were given training in guerrilla

warfare. It was estimated that there were nearly 400 hard-core

hostiles in each area, apart from hundreds of loosely organised

part-time reservists. Meanwhile, the last war (1973-77) involved

more that 55,000 Baloch guerrillas at various stages of the

fighting, and almost every section of the Baloch population was

affected in central and eastern Balochistan by this war. A

similar evolutionary process seems to have happened in Iranian

Balochistan, after the erosion of central authority in Iran

following the overthrow of the Shah in 1979, made the prospects

for Baloch nationalism appear more promising in Iran than in

Pakistan.

Though the seeds of Baloch nationalism were sown in Balochistan

in the colonial era, but its full flowering occurred as a result

of centralising policies of the modern post-colonial states of

Pakistan and Iran, which contradicted and restrained the

historical high degree of cultural and political autonomy of

Baloch populace. To a large extent the sporadic Baloch uprisings

in Pakistan helped in forging a political consciousness amongst

general Baloch populace; based on common ethnic, cultural and

historical ties transcending tribal loyalties.

The Cold War,

however, led indirectly to the weakening of the Baloch national

movements both in Iran and Pakistan. Because both the countries

were to be America’s allies against Soviet expansion in the Gulf

region, the United States was prepared to support them in

furthering her own foreign policy initiatives. Since the West

supported Tehran and Islamabad, so the Baloch turned to Baghdad

and Kabul. Thus the U.S. policies indirectly helped to

strengthen the two countries in their attempts to suppress the

Baloch movement for self-rule during the whole Cold War period.

In this regard, the Iranians’ use of the U.S. supplied arms

against the Baloch movement in 1973-77 is the most striking

example.

The political situation of Baloch

today reflects two contradictory tendencies. As the old warrior

Sher Mohammad Marri in the early 1990s stated, “Baloch

nationalism has penetrated the masses and is not confined to the

Nawabs and Sardars alone”.[5]

The urbanization, detribalisation and the migration of the

Baloch people to the cities of the region, have contributed to

the development of mass national consciousness. Yet their

political leaderships have often fallen prey to internal

divisions on both ideological and tribal lines. Divisions

between the Balochs’ political parties started with Zia’s

party-less elections in 1985, and later it sharpened during the

so-called 1990s democracy. The regional aspect of the Baloch

issue, as well as the growing complexities of Baloch society

have greatly complicated the task of the Baloch national

movement in achieving unity and a coherent strategy to achieve

their goals.

The material

analysed above warrants the conclusion that the Baloch form a

distinct nation and that their national consciousness is strong

enough to consider their national movement as having deep roots

in the convictions and aspirations of that nation. The divisive

factor of tribal loyalties will tend to play a constantly

diminishing role because of the impact of modern civilization,

which is changing the cultural patterns in the whole southwest

Asia. The paper also attempted to connect the Baloch problem

with the past policies not only of the Baloch inhabited states

but also of the Great Powers in an effort to demonstrate that no

Great Power interested in the region can afford to ignore the

Baloch problem or avoid the formulation of a Baloch policy as

part of an over-all Southwest Asian policy.

[1]

See Ahmed, Aijaz. 1992. ‘The national question in

Baluchistan’, in S. Akbar Zaidi (ed.) Regional

Imbalances, p. 214 ;Ahmed, Feroz. 1974. Ethnicity and

Politics in Pakistan. Karachi: Oxford University

Press., p.175; see also White Paper on Baluchistan.

1974. p. 39.

[2]

Daily Balochistan Express, Sunday, 6 May 2001.

[3]

Nek Buzdar, “Social Organization, Resource use, and

Economic Development in Balochistan” in: Monthly

Balochi Labzank, Hub (Balochistan), March-April

2000, p. 76.

[4]

Abbas Jalbani, “Can Balochistan Survive?” in: The

Herald, March 1992.

[5]

The News International, 3-9 July 1992.

No comments:

Post a Comment