Two main types of ethnic cores are the foundation for creating nations: the lateral and vertical. Exploring the lateral route first, we find that autocratic ethnic groups have the potential for self-perpetuation if they can incorporate other population strata.

However, many of these lateral ethnic groups fail to do so, leading to the disappearance of their cultures along with the demise of their states. Some lateral ethnic groups survived by developing and preserving a sense of common descent and shared memories. Others incorporate new ethnic and cultural elements into their foundational myths, symbols, and memories, spreading the cultural identity to a broader population. The Castilians provide a successful example of this cultural incorporation and expansion, forming the core of a Spanish state that expelled Muslim rulers and nearly united the Iberian Peninsula.

However, Franks and Norman's achievements, which proved historically significant, overshadowed Castilian success. In all three cases, lower strata and outlying regions gradually become incorporated into the state, grounded upon a dominant ethnic core. The Castilians achieved this through administrative and financial measures and by rallying parts of the population for inter-state conflict. The upper-class ethnic groups evolved a strong and stable administrative apparatus, which provided cultural regulation and defined a new and broader cultural identity. The upper-class culture set its stamp on the state and the evolving national identity, resulting in varying degrees of accommodation between the upper-class culture and those prevalent among the lower strata and peripheral regions.

An example of this cultural fusion and social intermingling is evident in the development of the English nation. Following the Norman Conquest, considerable intermarriage, linguistic borrowing, and elite mobility led to a fusion of linguistic culture within a common religious and political framework. There was substantial cultural fusion and social intermingling between Anglo-Saxon, Danish, and Norman elements.

The Scottish wars helped to bring together different ethnic communities. Although the English nation had not fully formed by the late fourteenth century, there were signs of integration and unity. Economic unity was still developing, and boundaries with Scotland and France remained disputed. A public mass education system and common legal rights were established in England later.

The entire development of these civil elements of nationhood would have to wait for the Industrial Revolution and its effects, especially from the thirteenth century onward. The Anglo-French and Scottish wars further served to unite the disparate ethnic communities. Although the English nation had not fully formed by the late fourteenth century, there were signs of integration and unity. Economic unity was still developing, and boundaries with Scotland and France remained disputed.

Developing these civil aspects of nationhood would require the Industrial Revolution and its effects.

The ethnic elements of the nation were well-developed by the fourteenth century or slightly later. Common names and lineage mythology, initially popularised by Geoffrey of Monmouth, were widely embraced, along with various historical recollections fueled by conflicts in Scotland and France; there was a strong sense of unified culture rooted in language and ecclesiastical structure, fostering solidarity despite internal class divisions and a deep attachment to the island kingdom. The foundations of a unitary state and compact nation were established by a Norman group that integrated the Anglo-Saxon population into its regal administration.

However, the ideology of Englishness did not emerge until the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when the old British myth was replaced by a more potent middle-class Saxon mythology of ancient liberties.

A similar process of bureaucratic incorporation by an upper lateral ethnicity can be seen in France. During the Christianized Merovingian dynasty, upper-stratum Frankish culture merged with the native Romano-Gallic culture.

However, a unified reign only became evident in northern France towards the end of the twelfth century. During this period, ancient myths of Trojan ancestry were revived and applied to the Franks.

It is a fact that an originally Frankish ruling-class ethnie succeeded, after many challenges, in establishing a relatively efficient and centralised royal administration over north and central France (later southern France). The royal administration facilitated the development of a unified economy and linguistic and legal standardisation within a compact territory, which, from the seventeenth century onwards, catalysed the formation of the French nation as we recognise it.

However, many regions retained their local character even after the French Revolution; the process was not completed until the end of the nineteenth century.

The Third Republic transformed peasants into Frenchmen by applying Jacobin nationalism, mass education, and conscription.

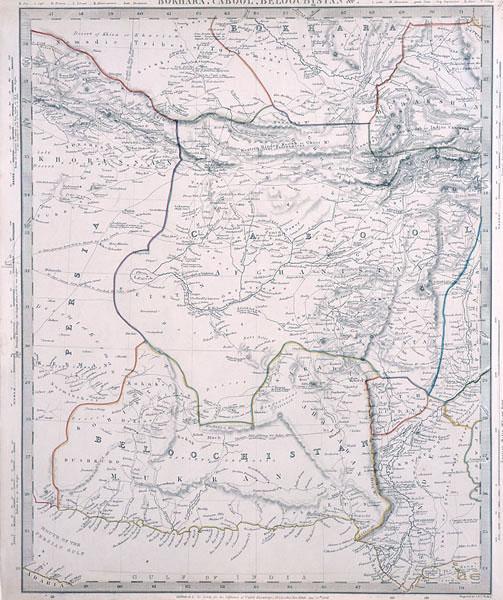

Spain underwent a significant transformation as the Castilian kingdoms resisted Muslim power and subsequently used a religious community to homogenise the kingdom of Aragon.

The expulsion of non-conformists such as Jews and Moriscos, along with the concept of "limpieza de sangre, " contributed to the unity of the Spanish crown.

Despite the independence of the Portuguese and failed Catalan revolts, Spain remained a polye-thnic state with distinct Basque, Galician, and Andalusian identities. The rise of ideological nationalism in the 19th century led to varying degrees of autonomous development among these ethnic communities. However, they shared an overarching Spanish sentiment and culture.

England, France, and Spain can be attributed to the development of modern nations due to their military and economic power during the rise of nationalism. England, France, and, to an extent, Spain developed rational bureaucratic administration, merchant capital, urban centres, and professional military forces, laying the foundation for the nation.

Some argue that the state created the nation by instilling a sense of corporate loyalty and identity in its subjects. While the state was indeed crucial for the formation of national loyalties, its operations were influenced by earlier assumptions about kingdoms and peoples and the presence of core ethnic communities. In England and France, this process of ethnic fusion was possible due to a relatively homogeneous ethnic core, which was essential for the development of homogenising states and the concept of the nation.

The rediscovery of the ethnic past

The process by which common ethnic groups may form the basis for nations is indirectly influenced by the state and its administration, unlike the route of bureaucratic incorporation by lateral ethnicities. It is typically the case because these groups were either subject communities or because, as seen in Byzantium and Russia, the state represented interests that those interests were partially outside its core ethnicity. This distinction also gives rise to intriguing variations in fundamental political myth, or mythomoteur, of vertical ethnicities.

In whole communities, cultural myths and values are passed down from generation to generation and spread across the community territory and social hierarchy. These achievements were made possible through organised religions, which had sacred texts, rituals, clergy, and sometimes secret knowledge. The social aspects of salvation religions, in particular, have helped these cultural traditions persist and have influenced the identities of different ethnic groups. For example, among Orthodox Greeks, Russians, Monophysite Copts, Ethiopians, Gregorian Armenians, Jews, Catholic Irish and Poles, myths, symbols, rituals, and sacred texts have played a crucial role in preserving traditions and strengthening social bonds within the community.

The hold of an ethnic religion posed critical challenges for creating nations from religious communities. People are shaped by religion, and their identity is deeply connected to the symbols and structure of an ancient faith. They often struggle in their attempts to become nations, and their intellectuals may find it hard to move beyond the conceptual framework of a religious-ethnic community.

Many members of such ethnically defined groups assumed that theirs was already and had always been a nation. According to some definitions, they were indeed a nation that possessed all the essential ethnic components of one. For example, Arabs and Jews shared common names, ancestral myths, memories, and religious cultures, ties to an original homeland, and a strong sense of ethnic solidarity when subdivided. Did this not meet the criteria of nationhood?

All they needed was to achieve independence and establish a state for the community.

The transition from ethnie to nation for the Arab and Jewish communities was not straightforward. Apart from geopolitical challenges, internal social and cultural factors made the process difficult. The geographic spread of the Arab nation contradicted the ideal of a compact nation in a defined area. Additionally, the varied histories of different Arab sub-divisions, the impact of modern colonialism, and the influence of Islam on Arab identity created complexity and ambiguity, overshadowing efforts to rediscover an Arab past.

The Jews faced challenges due to their geographic dispersion. as they lacked recognised territory and were exiled from their ancient homeland. While they had some educational and legal opportunities in certain areas, they were restricted in many ways and were forced to occupy specific economic roles in Europe. Additionally, there were conflicting attitudes and self-definitions within Judaism and its rabbinical authorities, which created obstacles to national unity. It was only later that some rabbis and a faction of Orthodoxy began to support Jewish nationalism and the Zionist project, despite traditional hopes for a messianic restoration to Zion. The concept of Jewish self-help had become foreign to the medieval interpretation of Judaism, and the prevailing belief that the Jews were a nation in exile perpetuated a sense of passivity.

Amid declining communities and Western expansion, a new group of secular intellectuals emerged as the populace resigned. Their primary goal, as they understood it, was to change the connection of a religious tradition with its leading followers, the ordinary people. Consider this development in the broader context of a series of socioeconomic, political, and cultural revolutions that started in the early modern period in the West. As mentioned, the main driving force behind these changes was establishing a new professionalised bureaucratic state based on a relatively homogeneous ethnic group.

Attempts by older political groups to adopt some aspects of the Western rational state to make their administrations and armies more efficient disrupted the traditional arrangements of these empires with their diverse ethnic groups. In the Habsburg, Ottoman, and Romanov empires, increased government involvement, growing urbanisation, and trade renewed pressure on various ethnic groups. The spread of nationalist ideas from the late eighteenth century onward brought new ideals of cohesive population groups, representation for the people, and cultural diversity, which influenced the ruling classes of these empires and especially the educated members of their subject communities.

Attempts by older political groups to adopt certain aspects of the Western rational state to make their administrations and armies more efficient disrupted the traditional arrangements of these empires with their diverse ethnic groups.

In the Habsburg, Ottoman, and Romanov empires, increased government involvement and growing urbanisation and trade put renewed pressure on many different ethnic groups. The spread of nationalist ideas from the late eighteenth century onward brought new ideals of cohesive population groups, representation for the people, and cultural diversity, which influenced the ruling classes of these empires, especially the educated members of their subject communities.

Transitioning from passive peripheral minorities to an active, assertive, and politicised community with a unified policy; Striving for recognition of a homeland for the community, with a clearly defined territory; Economic integration of all members within the demarcated territory, with control over its resources, and moving towards economic self-sufficiency in a competitive global context; Granting legal citizenship to ethnic members, mobilise them for political purposes, and bestowing upon them equal civil, social, and political rights and responsibilities; Placing the people at the core of moral and political considerations and promoting the new role of the masses through.

The traditional elites, especially the custodians of sacred texts that have long defined the community, may resist the changes, as expected. It means that intellectuals should present their new ideas using ancient symbols and formats to redefine the community. These presentations are not just manipulations, although individuals may manipulate them, like Tilak's use of the Kali cult in Bengal. There's no need to reveal what a selective interpretation of the ethnic past is. However, this selection can only happen within strict limits set by existing myths, symbols, customs, and memories of a community.

Mehrab Sarjov is a political activist in London striving for an independent Baluchistan.