“we appear on the brink of yet another nation-state baby boom. This time, the new countries will not be the product of a single political change or conflict, as was the post-Soviet proliferation, nor will they be confined to a specific region. If anything, they are linked by a single, undeniable fact: history chews up borders with the same purposeless determination that geology does, as seaside villas slide off eroding coastal cliffs.”

Here is their list of potential geopolitical changes to look out for. The links below are to numerous GeoCurrents posts about these “potential countries”.

1. Mali Breaks Up

2. Belgium (Finally) Splits Up

3. Congo Splinters

4. Somalia’s Breakup Confirmed

5. Alawites Go Solo

6. The Arabian Gulf Union

7. An Independent Kurdistan

8. Greater Azerbaijan

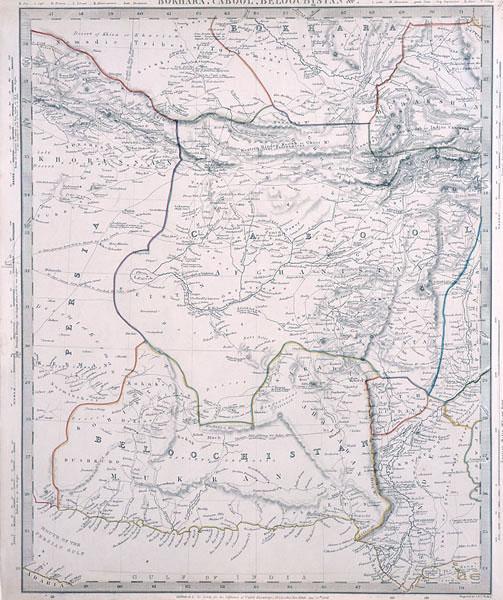

9. Pashtunistan and Baluchistan Take a Stand

10. China Gobbles Up Siberia

11. Korea Reunited

Source: http://geocurrents.info/geopolitics/new-york-times-list-potential-new-countries-others-well#ixzz2gpW6opAS

Source: http://geocurrents.info/geopolitics/new-york-times-list-potential-new-countries-others-well#ixzz2gpW6opAS

Both Berber nationalism and the rise of radical Islam led to the separation of Azawad, Mali’s vast northern Sahara territory, which the Tuareg rebels declared as an independent territory on April 6, 2012. What has remained unmentioned in most media reports, including the NYT article, however, is the ethnic diversity in Azawad: the relatively densely inhabited southern part of this self-declared state is occupied largely by non-Tuareg peoples, which complicates the political situation considerably.

Jacobs and Khanna describe Belgium as “divided along linguistic lines between French and Flemish speakers … drifting toward a split for decades”. The country’s unusual political history is often blamed for the crisis of the Belgian state. But the division into Flemish-speaking north and Francophone south is not as clear cut as many pundits describe it.

According to Jacobs and Khanna, in DRC “the state is so weak that some experts question whether it can be said to substantively exist at all” andGeoCurrents once called it a “Potemkin State”. Ethnic incoherence and economic strife, as well as its other geographical challenges, have been tearing the country for decades. Whether it actually falls apart and whether any parts of it will remerge with other existing countries remains to be seen.

Jacobs and Khanna see the recent events in Somalia as the country’s “best chance to emerge from decades as the world’s poster child for state failure”. They note further that “Puntland and Somaliland, the eastern and western thirds of the country, want no part in the party as they continue to build their own economies, largely around pirating, and operate their own administration and police forces”. But given that Somalia’s official government cannot even control Mogadishu, the fact that Somalia claims Somaliland and Puntland means little. There is also a interesting question of whether Puntland has anything to do with the historical Land of Punt—the answers appears to be “not much”. Somaliland, for its part, is a relatively well governed state that has little if any connection with piracy.

Jacobs and Khanna’s #5 is even more timely now than it was a year ago. They describe several possibilities for the “new Syria”. One is that it would “resemble its erstwhile client state Lebanon: religions exerting squatters’ rights in the empty shell of central government”. Another possibility is that it would “revert to the ethnic puzzle laid out by the French: separate states for the Druse and the Alawites, and city-states for Damascus and Aleppo. The Alawite state, home to the dominant sect in Bashar al-Assad’s Syria, would control the fertile, mountainous coastline and is perhaps the most viable contender for separate statehood”. The ethno-religious complexity of Syria is described in great detail in a GeoCurrents post from two years ago. We find it curious that the Druze, who dominate the Jabal al-Druze volcanic plateau in southern Syria, are almost never mentioned in current reporting on the Syrian civil war.

Jacobs and Khanna consider the possibility of both Bahrain and Yemen joining Saudi Arabia, though the backgrounds of the two imagined mergers would be entirely different. What unifies these Sunni Arab monarchies is a common threat from Iran.Yemen, however, is often characterized as a failing state, while Bahrain’s territorial disputes with Iran may bring it closer to Saudi Arabia. Bahrain’s Shiite majority, however, makes this issue especially complex. Jacobs and Khanna’s map further showsOman becoming another member of this potential “Arabian Gulf Union”. Although a number of problem are faced by the royal dynasty in Oman, the fact the country has neither a Sunni nor a Shiite majority, but rather one of the stand-offish Ibadi sect, makes such a merger highly unlikely.

Another potential Middle Eastern newcomer in the geopolitical club is an independent Kurdistan, unifying Kurdish territories in Iraq, Iran, northern Syria, and Turkey. In the very least, an independent Kurdish state may arise in northern Iraq, where “the Kurdistan Regional Government … is by far the country’s most stable sector, flying its own flag and cutting energy and infrastructure deals on its own with Exxon and Turkish firms”, state Jacobs and Khanna. But the relationship between the Kurdistan Regional Government and the area’s Christian community are complicated, to say the least. Yezidis is another fascinating religious sect in the region. Kurdish populations in Syrian, Turkey, and Iran face their own very different challenges.

According to Jacobs and Khanna, Iran is “at risk of internal implosion”, with Azeri speaking northwestern part of the country potentially splintering off and joining with already independent Azerbaijan. Azeris on both sides of the border are ethnic Turks speaking a Turkic language and there has been some rapprochement between Iran and Azerbaijan in recent years. Still, Iran’s Azeris show few signs of seeking autonomy, much less independence or union with Azerbaijan. Moreover, Iranian nationalistsdreaming of “the Greater Iran” virtually always include the Azeri-speaking territories into Iranian sphere. Iranian Azeris are far from marginalized, and many are strong supporters of the Iranian state.

Jacobs and Khanna predict that “with no cohesive figure in sight to lead Afghanistan after President Hamid Karzai, and with Pakistan mired in dysfunctional sectarianism and state weakness, a greater Pashtunistan could coagulate across the Durand Line, which divides the two countries”. Afghan identity is indeed a complex and contentious issue. Moreover, Jacobs and Khanna see a possibility of the gas-rich Baluchistan gaining independence. It is important to note that the leaders of the self-proclaimed Baluchistan include the Iranian Balochistan within its boundaries, which is bound to cause problems with Iran.

Jacobs and Khanna see a real possibility of China “taking over large chunks ofSiberia, part of Russia’s failing and emptying East”. They describe the current situation as follows:

“Hundreds of thousands of Chinese have already crossed the border at the Amur River and set up trading settlements, intermarrying with Russians and Siberia’s native nomadic minorities. Russia has a nuclear arsenal with which to fend off formal threats to its sovereignty, but the demographic imbalance is to Russia’s disadvantage and could accelerate the economic shift in China’s favor. Russia’s far eastern outpost of Vladivostok is ever more distant from Moscow.”

GeoCurrents, however, does not believe that China poses a realistic geopolitical threat to Russia. Whether Russia will fall apart into a number of smaller states is another fascinating question, however, which GeoCurrents considered in detail in two separate posts.

According to Jacobs and Khanna,

“In an echo of German unification, a collapse of the North Korean regime would pave the way for the militarized border to open up and disappear. In fact, South Korean strategists are already quietly building a regional coalition to manage the economic and social costs of absorbing the hermit kingdom.”

How well such potential integration of North Korea may go is not clear, however, and even South Korea remains characterized by intense regionalism in politics, as is evident from recent election returns. For all of that, however, Korean nationalism remains a potent force.

Additional suggestions for potential new countries have also been made elsewhere. ComingAnarchy.com lists the following newly independent states that could splinter off existing countries in Europe: Scotland(currently part of the UK), Normandy, Brittany, and Corsica (France), Basque Republic and Catalonia, the latter with or without the Balearic Islands (Spain), Baden-Württemberg and Bavaria (Germany), Padania andSardinia (Italy).

An even more radical map of “Potential independent states in Europe” (whose original author I was not able to establish as it has been reposted on multiple websites without proper reference) lists, in addition to the already mentioned candidates: United Ireland, created by joining together the current Republic of Ireland and the Northern Ireland) and Wales in the British Isles; Galicia and Andalusia (Spain); Trentino South-Tyrol in northern Italy; Republica Srpska and Herzeg-Bosnia (which together currently form Bosnia and Herzegovina); Kosovo and Metohia in southern Serbia; Trasdnistria; North Ossetia, Chechnya, and Abkhazia in northern Caucasus region; Nagorno-Karabakh; and Northern Cyprus.

GeoCurrents has written extensively about these problematic regions and nationalist movements (follow links above), butCatalonia in particular is worth mentioning in view of the 250-mile human chain created in support of Catalan independence on 11 September 2013. Approximately 1.6 million people in Spain participated in this event, which became known as The Catalan Way towards Independence, or simply The Catalan Way. It was organized by the Assemblea Nacional Catalana (Catalan National Assembly), an organization that seeks the political independence of Catalonia from Spain through democratic means. Catalan nationalists have chosen public demonstrations and electoral politics over violence, in sharp contrast to hard-core Basque nationalists, who have long embraced militancy, attacking the Spanish state and its institutions with bombs and guns. It appears that the Catalan strategy has been much more successful than that of the Basques. Not just Spaniards at large, but the majority of Basques themselves have been so disgusted with the terrorism of the separatist ETA (Euskadi Ta Askatasuna) that the movement for Basque nationhood has lost its impetus. Catalan nationalism, by contrast, is gaining ground.

One of the reasons behind the Catalan independence movement is the desire to protect the local culture, which revolves around the Catalan language. Like Spanish, Catalan is a Romance language that evolved from Latin after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century CE. But despite being spoken in the Iberian Peninsula, Catalan is more closely related to French and Italian than to Spanish. For example, the Catalan word for ‘summer’ is estiu, derived from the same root as Frenchété and Italian estate but not Spanish verano. Similarly, the verb ‘to want’ in Catalan is voler, closely related to the Frenchvouloir and Italian volere, whereas Spanish querer is clearly different. Both Catalan and Spanish incorporated words from Arabic, but not necessarily the same ones: Catalan borrowed alfàbia meaning ‘large earthware jar’ and rajola meaning ‘tile’, whereas Spanish adopted aceite and aceituna, meaning ‘oil’ and ‘olive’, respectively.

The Catalan language, however, is not limited to Catalonia. It is the national and only official language of the tiny country of Andorra, and a co-official language of the Balearic Islands and Valencia in Spain. It is also spoken, without official recognition, in parts of Aragon and Murcia in Spain, and in the French region of Roussillon. Because Catalan culture extends well beyond Catalonia, many sources explain the surging Catalan independence movement in economic rather than cultural terms. Catalonia is one of the wealthiest parts of Spain, and the taxes collected there subsidize the poorer parts of the country. With Spain’s current economic crisis, many of the region’s residents feel that they can no longer afford to support Extremadura and other poorer parts of the country. Such economic issues have the potential to bind indigenous Catalans with migrants from other parts of Spain who now live in the region.

The Spanish constitution bans outright votes on secession, and it is unclear whether most Catalans want full independence or merely enhanced autonomy. Even so, Catalonia appears to be well on the path “by which the citizens of Catalonia will be able to choose their political future as a people”, as stated in the recently adopted Catalan Sovereignty Declaration.

Finally, another territory that has not been mentioned in those lists of potential independent states is Vojvodina. In late 2009 Serbia granted its northern area of Vojvodina control over its own regional development, agriculture, tourism, transportation, health care, mining, and energy. Vojvodina, population two million, even gained representation in the European Union (although it will be allowed to sign only regional agreements, not international ones). Autonomy rather than independence, however, appears to be what the majority of local residents, 65% of whom are Serbian, want. Vojvodinans evidently favor autonomy largely for economic reasons. But claims for heightened self-rule can lead to further claims; already a local ethnic Hungarian group wants its own autonomous zone within the larger autonomous area of Vojvodina.

http://geocurrents.info/geopolitics/new-york-times-list-potential-new-countries-others-well

No comments:

Post a Comment