Feb 24 2014 By Willem Marx

Rumor and reporting are unavoidably intertwined in Pakistan.

Hamid Mir appeared quietly

satisfied. The normally voluble television anchor for Geo News sat in

an editing booth in Islamabad last February, watching intently through a

series of interviews he had conducted earlier that week. On the

computer screen’s editing window he pressed young children to describe

the sound of Army bombardments, before encouraging brightly dressed

Baloch women to explain how their sons, nephews, or husbands had been

“disappeared.” This occasionally inflammatory reporter (who famously

found an incendiary device attached to the underside of his car) had

just returned from 48 hours in Balochistan, where he had been reporting

on the effects of the ongoing conflict there.

Mir seemed genuinely enthusiastic about this rare

opportunity to counter the “official” and sanctioned narrative about the

insurgency there. But there was also no disguising the relief he felt

that he and his crew had returned unscathed, and a certain exuberant

relish for having done so in spite of innumerable government obstacles.

“Getting access is so difficult,” he acknowledged, as he and his editor

fast-forwarded through the clips. I told him I could sympathize.

As the author of a new book about the region, Balochistan at a Crossroads,

I have spent some rewarding but challenging weeks in the remote deserts

and mountain ranges of Pakistan’s largest province. The vast and

sometimes inhospitable interior remains almost completely off-limits to

foreign journalists and just a handful have reported there extensively

over the past decade. As a consequence, the province’s conflicts and

horrors garner very little international attention: Baloch insurgents

continue to wage a low-intensity war against the Pakistani military and

civilian targets; military intelligence agencies allegedly kidnap young

Baloch activists before dumping their bodies on roadsides; border

authorities by turns combat and connive with cartels smuggling Afghan

heroin; Sunni extremists target Hazara pilgrims in mass bombings; and

Afghan Taliban rest up their war-weary limbs during Quetta’s harsh

winter months.

And while every number of these should warrant further

media scrutiny, amongst these varied narratives I have found that the

Baloch insurgency, a major focus of Balochistan at a Crossroads, is perhaps the storyline that Pakistani authorities want publicized least of all.

My friend and collaborator Marc Wattrelot—a talented

French photojournalist whose emotive black and white images haunt the

pages of our new book—will tell you that writing, editing and

type-setting has proved to be a time consuming and at times exhausting

process for the two of us. But he also likes to joke that these

exertions pale in comparison to the patience and luck required in

successfully reaching and reporting from Balochistan during our visits.

But for the region’s local reporters, such attributes

have hardly proved sufficient when it comes to their long-term survival.

Shahzad Zulfiqar is a veteran Quetta-based journalist and has written

for the Herald, Newsline and The Nation and reported on

Balochistan for Samaa TV, crisscrossing the province from Dalbandin to

Gwadar to Khuzdar and everywhere in between to interview insurgent

commanders repeatedly over the course of two obstinate and brave

decades.

He says that at least 22 journalist colleagues have been

killed in the past four years; local militant groups claimed six of

those murders, and security forces dispatched the remaining 16, family

members of the victims tell him. Local reporters are increasingly caught

between militants with Baloch nationalist aspirations who wish to

control the narrative for their own purposes, and a security apparatus

that wants to starve those same militants of any and all potential

publicity.

During a recent phone call with Zulfiqar, I asked him to

enumerate the expanding threats that loom over the shrinking local

press corps today. “On the top of the list are the intelligence

agencies,” came his immediate answer. “Second is the Frontier Corps, the

paramilitary forces.” Sunni extremist groups like Lashkar-e-Jhangvi

were a close third, he continued, followed by the Baloch insurgent

groups. “These are all people who don’t spare journalists,” was his

matter-of-fact conclusion.

Zulfiqar was once fired from his job after he recorded

an on-camera interview with an Iranian Baloch militant called Abdulmalik

Rigi—a solicitous but zealous young man I had also met with on a

previous occasion. Rigi was subsequently captured in uncertain

circumstances and executed by Iran’s authorities, but just by talking to

him in person Zulfiqar had exposed himself to official hostility.

Senior security officers in Balochistan were apparently embarrassed

because their Iranian counterparts had chastised them for allowing a

local journalist to interview Rigi, at the time Iran’s most sought after

terrorist. The senior officers immediately redirected their ire and

made their displeasure known to the employers of this veteran reporter

who had simply been doing his job.

Far worse was to come though, when Zulfiqar helped

arrange an interview for an American newspaper reporter, Carlotta Gall,

and photographer Scott Eells, with an ageing aristocratic figurehead of

the Baloch insurgency, Nawab Akbar Bugti. Gall, who reported for The New York Times

in Pakistan and Afghanistan for many years, said the visit was her

first to Balochistan. “To go on and then obviously see the rebels, that

was extraordinarily difficult and a bit risky,” she recalls now. “And it

was certainly risky for the people who took us in.” Following a

grueling journey into the mountains southeast of Quetta, and some time

spent with Bugti and a small cadre of his tribesmen, her American

newspaper splashed the scoop. “The ISPR and military were furious about

my story about Bugti,” says Gall, who is now the Times’ correspondent for North Africa. “There was a big picture of him on the front page of The New York Times, and the military spokesperson said, ‘you made him into a hero.’ They were furious.”

Zulfiqar, who had acted as the go-between and travel

companion for Gall and Eells on the trip, became the easiest target for

that fury. “When I came back to Quetta they called me, ‘please let’s

have a cup of tea.’” He went to meet a brigadier from Military

Intelligence, who immediately began to shout at him. “‘Forget about

journalism, when you enter my room, you are an anti-state element,’” the

military man apparently scolded him. “‘Why have you taken these

bastards? How many dollars did you receive from these Americans?’” This

was his last warning, Zulfiqar was told in no uncertain terms: “‘Next

time you will bear the consequences.’” The higher-ups had allegedly

instructed the brigadier, “‘make him understand, or if not, perish

him.’”

Zulfiqar kept his head down for a while, and refrained

from asking difficult questions of security leaders at Quetta press

conferences. “I stayed silent,” he admits.

International journalists readily accept how dangerous

it is for locals like Zulfiqar who help them in Balochistan; Gall told

me that at least one other person who helped her on a story in the

region was subsequently forced to flee the country. An interpreter Marc

and I both worked with, and to whom our book is dedicated, passed away

very suddenly a couple of years ago. Recently some of his friends

contacted me to say that his family members now suspect that security

agents, angered by his political activities, may have poisoned him.

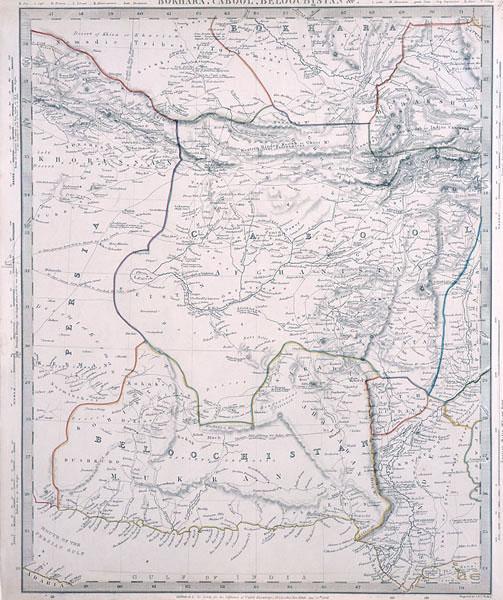

Courtesy of Marc Wattrelot

Like many such allegations leveled in Balochistan, it is

hard to separate fact from fiction. However, I am more certain about

the fate of another young Baloch translator, who hails from the Iranian

side of the border; in 2007, he helped me interpret my interview with

the militant commander Rigi. After Iranian and Pakistan authorities

sought to arrest him for this daylong assignment with me, he has

subsequently sought and won political asylum from the UNHCR, and we are

together working to find him a new home inside a safe European nation.

Other more high-profile journalists have been forced to

flee Balochistan, including Ayub Tareen of the BBC, who in 2012 told

Reporters Without Borders he had faced death threats from a militant

separatist group for reporting on their movement in what they alleged to

be a partisan manner. And Malik Siraj Akbar, the star Baloch reporter

of his generation who now lives in D.C. after winning political asylum

in the United States, wrote that his decision to leave Balochistan was

in part driven by the deaths of a dozen journalist friends over the

course of a single year.

The departure of journalists from Balochistan—or worse,

their targeted killing—can have a chilling effect on their peers who

remain. And the result, as Ahmed Rashid has pointed out, is

“self-censorship” as a form of self-preservation. But such violent

infringements on press freedom rarely warrant attention outside the

region unless a foreign journalist is involved. The New York Times’

Gall became an unwilling poster child for this phenomenon, after

Pakistani government agents famously punched her in the face at her

Quetta hotel in 2006, before confiscating her reporting notes and a

laptop.

“I think Balochistan has been very important to the

Pakistan military, to run their operations there, to be able to control

the Baloch tribes, to be able to do as they please,” posits Gall.

“That’s why diplomats can’t travel there, that’s why journalists get

hassled there. And I think my treatment was designed to deter others.

Ultimately other journalists got scared, who see what happened.” Gall

says her profile of Bugti’s struggle against Musharraf’s military state

was the first time she truly antagonized Pakistan’s security forces. A

subsequent trip to Waziristan and an attempt to report on Afghan Taliban

presence in Quetta only angered the authorities further, and ultimately

all this led to her physical assault. “From then on I had great

difficulties with visas,” she told me on the eve of a recent reporting

trip to Libya. “I think I was blacklisted.”

The first and often greatest obstacle for any foreign

reporter wishing to report inside Balochistan is simply getting your

hands on a journalist visa. Then to travel outside major cities, you

will also require a “No Objection Certificate” as an accompaniment to

the visa in your passport. This piece of faxed paper signed by various

government entities, all of which state that they have “no objection” to

your travel plans, is from my experience far more important than a

passport when visiting many of the more troubled districts of the

province. And consequently it remains the primary means by which foreign

journalists who visit Pakistan are prevented from traveling easily

outside Lahore, Karachi and Islamabad. The ostensible reason for such

restrictive measures is to safeguard overseas visitors, but in the view

of most foreign journalists I have spoken with, the often Kafka-esque

process for obtaining an N.O.C. is also important as a tool for

discouraging the kind of enterprise reporting that might well uncover

some unwelcome truths.

Horror stories about Pakistani visa bureaucracy abound

among the foreign press corps, but my own nadir came in the autumn of

2008, as I tried to obtain a journalist visa and N.O.C. that would allow

me to travel once more to Quetta. It involved dozens of early morning

and frustrating phone calls from London to low-level mandarins in

Islamabad, who repeatedly made promises that they just as often broke.

The unspoken reality, it turned out, was that access to the region is

not something the hacks from the External Publicity Wing could actually

grant me. My visit would require signoffs from Pakistan’s intelligence

agencies, including the ISI and MI. Fully three months later, after

interventions from several senior politicians, my request was granted.

But for some reporters who cannot abide such a wait, the solution is

simply to skip the process altogether.

“I wasn’t traveling there on a journalist visa,”

explained Karlos Zurutusa, a Basque journalist who wrote several

dispatches from Baloch areas inside both Pakistan and Iran. “I was

traveling on a visitor visa. The Pakistan Embassy in Madrid told me it

was very dangerous, I should fly to Islamabad, I should by no means

travel to Quetta.” But by claiming to be a history teacher interested in

ancient routes to India, he made it into Pakistan’s Balochistan

province from Iran. Zurutusa concedes that this approach carried other

risks with it. “The people who were helping me were horribly scared I

was putting them in danger.” He recently wrote a piece for Al Jazeera’s

website, inspired by his own experiences, that described Balochistan as a

“black hole for media.” Adrenaline was a major reporting tool when he

visited Baloch insurgent camps, he told me, but that could only last so

long. “I think I got to understand how dangerous it was once I was

outside.”

Declan Walsh and Nick Schmidle are two other reporters

who know all about being on the outside and looking back into Pakistan.

The Irishman Walsh, who is a successor to Gall at The New York Times, and the American Schmidle, who wrote a widely-read dispatch from Quetta for the Times and is now on the staff of the New Yorker, were

both forced to depart Pakistan involuntarily. And while the two were

not removed from Pakistan specifically for their reporting in

Balochistan, their departure certainly reduced by two the number of

Pakistan-based foreign reporters who were willing or able to report from

the troubled province. Other American reporters previously based in

Islamabad have told me that they were loathe to initiate undercover

trips into Balochistan, for fear of prompting their own expulsion from

Pakistan—which in turn would create headaches for their employers. “I

would say that yes, that is a worry,” says Gall, “but you should never

not do a story because you’re worried about your visa or your residency

being revoked.”

But if you do make it into the province, and encounter a

degree of freedom of movement, extracting verifiable facts and

obtaining accurate answers from the authorities oftentimes resembles a

dystopian exercise in onion-peeling. Rumor and reporting are unavoidably

intertwined elsewhere in Pakistan of course; the byproducts of

clamoring, competing and overtly political narratives. But Balochistan

too often suffers from quite the opposite—a dearth of public

information, unreliable sources, a lack of context and official

secretiveness.

“I don’t know if I would dare to do it again now,”

Zurutusa told me from the Basque country in northern Spain. “I wouldn’t

dare to step foot in Pakistan again.”

I have sometimes expressed a similar sentiment to friends and family

after trips to Balochistan, in which police officers have attempted to

smash my camera, or intelligence agents have physically detained and

interrogated me at the airport departure gate. But I’ll be back again

this weekend to talk about the conflicts still ravaging Balochistan. And

I am hopeful that no government agencies will try to stop me telling

the truth about what I’ve seen and heard, and learned.http://newsweekpakistan.com/between-fact-and-fiction/

From our March 1 & 8, 2014, issue.

No comments:

Post a Comment