Activists

fighting for a cause, especially one that has a lot of popular emotion

attached to it, are usually loud and shrill when holding forth in

public.

They tend to be belligerent and turn excessively aggressive if their views are contradicted.

In

a sense, loud speech, belligerence, and aggression are necessary for

effective activism. After all, if an activist is an easy pushover, then

his or her cause cannot be worth fighting for.

Pakistani soldiers in Balochistan: The Baloch were, and remain, a fiercely independent people

At

the same time, needlessly pushy activism can put people off and make

them indifferent to causes that could be perfectly legitimate and

deserving of support.

Hence

listening to Prof Naela Quadri Baloch at a recent discussion on

Balochistan organised by the Observer Research Foundation came as a

pleasant surprise.

She

was soft-spoken yet firm, persuasive yet polite. She presented her

case, or rather the case for a free Balochistan, without recourse to

either maudlin sentiments or theatrical hyperbole.

Much

of the story of Balochistan is uncluttered and uncontested, provided we

do not pay undue attention and attach unwarranted credibility to

Pakistan’s claims.

In

1947, when British colonial rule came to an end in the Indian

subcontinent, 535 princely states were given the option of either

acceding to India or Pakistan through merger of territory, or remaining

free and independent.

The

Khan of Kalat, which comprised nearly all of Balochistan barring three

minor principalities, was not too eager to accede to Pakistan.

A member of the Pakistan Navy at the Gwadar port in Balochistan Province

The

Baloch were, and remain, a fiercely independent people, with their own

cultural and social identity, along with a land endowed with natural

resources.

That early impulse for freedom became the root cause of Balochistan’s subsequent misery.

Since

its violent Caesarian birth, assisted by a scalpel-wielding Britain, on

August 14, 1947, Pakistan has been as deceitful as its Quaid-e-Azam

Mohammed Ali Jinnah was during his brief and bitter life as the ruler of

a moth-eaten country, one half of which fell off the map in 1971.

Jinnah the barrister helped the Khan of Kalat to prepare his brief for independence and a Standstill Agreement in the interim.

Jinnah the smash-and-grab politician paved the path for Kalat’s annexation by Pakistan on March 27, 1948.

Thus was Balochistan forcibly converted into a province of Pakistan, against the wishes of the Baloch and their Khan.

Balochistan’s

struggle against Pakistani rule and Islamabad’s ‘One Unit’ policy has

been relentless since the annexation of Kalat.

Brutal

repression by the Pakistani Army has failed to break the spirit of

resistance. Beginning with 1948-49, it has been a horrific campaign to

put down dissent and silence the voice of freedom.

There

are several similarities between the Pakistani Army committing hideous

crimes in Bangladesh (what was then East Pakistan) and Balochistan.

Mass

killings, the rape of women, laying human habitations to waste,

targeted assassinations - Bangladesh saw it all during its Liberation

War of 1971. And Balochistan continues to witness these horrors.

General

Tikka Khan, nicknamed the ‘Butcher of Bangladesh’, had the dubious

distinction of also being called the ‘Butcher of Balochistan’ for the

bloody campaign he led from 1973 to 1977.

But

for all the sorrow, grief and misery heaped on the people of

Balochistan, they have risen again. The freedom movement, relaunched in

2004, continues unabated.

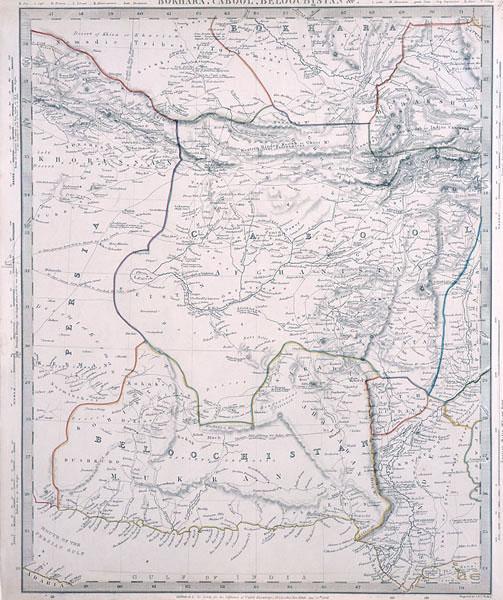

Divided

by the Goldsmith Line of 1871, Balochistan is split between Pakistani

and Iranian occupation, with some bits spilling into Afghanistan on

account of the flawed Durand Line.

Britain understood the strategic importance of Balochistan and played its game accordingly to keep the Russians out.

Today, both Pakistan and Iran are leveraging that strategic importance to further their own economic and security interests.

India’s

position on Balochistan has been, at best, ambivalent. Notwithstanding

the arrest of an Indian national (Pakistan claims he is a “R&AW

agent” and was arrested on its side of the Goldsmith Line; there are

credible claims he was arrested by the Iranians and handed over to the

ISI) it would be silly to imagine a grand Indian conspiracy in action.

New Delhi has long been incapable of doing what Mrs Indira Gandhi did in

1970-71.

Yet

there is a case for an Indian policy on Balochistan. India did play a

major role in propping up the Northern Alliance so as not to concede all

ground to the Taliban and its mentor, Pakistan, in Afghanistan.

A

hands-off approach, therefore, is lacking in precedence, even if we

were to discount India’s proactive role in the liberation of Bangladesh

from the tyranny of Pakistan. The issue is what should be that policy.

Investing

in Chabahar port that lies on the Iranian side of Balochistan cannot be

a policy in entirety. At best it will partially countervail China’s

captive port at Gwadar on the Pakistani side of Balochistan. That’s one

pawn moved.

What

next? One possible option is for India to declare moral and diplomatic

support for the freedom movement in Balochistan, while calling for a

peaceful resolution of the conflict.

That

would require gumption. Indeed, it would need the political courage of

Mrs Gandhi coupled with popular support for a righteous cause that India

believes in.

Great

nations and rising powers have to be risk-takers. The inevitable

backlash of supporting Balochistan’s liberation war will no doubt be

huge. But if Mrs Gandhi, prime minister of an impoverished nation, could

turn up her nose at what the world thought, surely Narendra Modi, prime

minister of the fastest growing economy, can do likewise.

A

successful Balochistan policy premised on India’s historical

association with just causes would also lead to the forging of a

successful Pakistan policy. Is the government game?

The writer is a political commentator

No comments:

Post a Comment