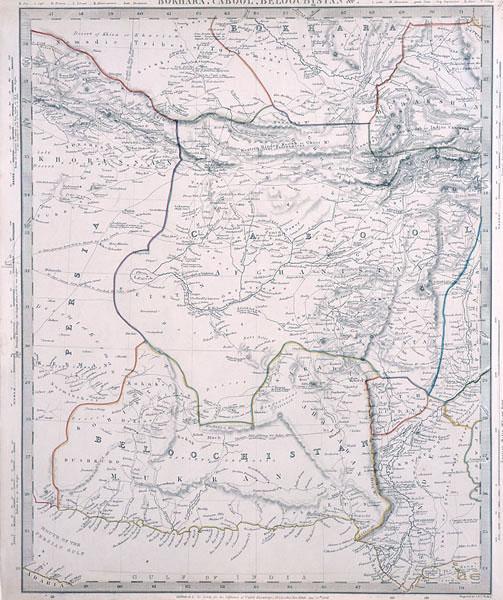

1n 1870-71 it was agreed that the disputed frontiers of Persia and Afghanistan should be solved through the arbitration of the British. The Persian Government appointed as Commissioner Mirza Masoum Khan, a senior diplomat, and the Government of India assigned, on the presence of the Afghan ruler Amir Sher Ali Khan, Major-General Frederick Goldsmid, Director of the British Telegraph Wire Construction as arbitrator.

The authorities in Bombay suggested involving the Muscat Arabs to the proceedings of Baluchistan boundary arbitration, because they had once leased Gwadar and Chahbahar from the Persian government.

1871 the British-Persian boundary commission concluded on behalf of the Persian Empire to buy its goodwill against the Russian Empire which annexed Central Asia. Panjgur, Parun, Kuhak, Boleida, Nasirabad to the eastward Dash belonged to Kalat, the frontier comprised Dizzak, Bampusht, Sarbaz, Peshin, Bahu and Dastyari, Sistan Western Makran and Sarhad which belonged to the Persian Empire. The question of Kuhak remained to be settled later. The Persian government did not agree with his decision on the northern section of that line. Kuhak, Esfandak, the Mashkil Valley, the remaining stretch of the frontier areas included a long space as far north as the river of Helmand in Sistan still remained under dispute.

In 1882 a boundary correction let Chahansur to Afghanistan. In 1893 the Durand Commission decided Helmand and Nimroz to join to Afghanistan.

The Persian reasserted their control on Kuhak, which motivated the British to seek delimitation of the still questioned boundaries. On December 27 1895, the two sides agreed in Tehran to demarcate the territories between Kalat and Sistan on the basis of Colonel Holdich’s final report on the proceedings of the Persian-British Baluchistan Frontier Delimitation Commission.

In 1896 the Persian-British border was finalised by the McMohan Commission without obtaining consent from the Khan of Kalat.

West Baluchistan under the Pahlavi Monarchy

The troops of Reza Khan the new Persian ruler defeated the troops of Khazan Khan, ruler of Khuzestan in 1925 and in 1928 gained victory over the revolt of Dost Mohammad Khan. Independent West Baluchistan was forcibly annexed to Iran by Reza Shah, who created a centralised Persian state. By Harrison the movement of Dost Mohammad was the prototype of Baloch nationalism. [2]

In 1932 the delegation the Baloch of Persia (from 1934 called Iran) participated in the All-Indian Baloch Conference in Jacobabad. Magsi, the chairperson of the conference paid a visit in Sarhad just before the gathering.

Reza Shah took measures to abolish the nomadic pastoral economy, intended to settle the nomads, introduced land register, the pastures which were considered community property before, were registered on the names of the chieftains who moved to urban centres.

Sporadic Baloch revolts accompanied Reza Shah’s rule. In 1931 Barakat Khan of Jashk, in Sarhad Juma Khan Ismailzai and Jiand Khan Yarahmadzai took arms. Their revolts were supressed by air force deployment. The next revolt In 1938 in Kuhak was led by Mehrab Khan Nausherwani. The last uprising was of Mirza Khan in Jashk. These tribal uprisings had local, patrimonic and tribal character and they lacked the modern social base of nation building.

In 1937 from Western Baluchistan the administrative unit of Hokumat-i Makran, then Hokumat-e Baluchistan was formed. The provincial centre Duzzap, was renamed to Zahedan.

The Baloch of Western Baluchistan are nomads with large-range action radius of migration with great livestock crossing regularly for pastures the artificial state borders. The tribal system was preserved among them.

In Iranian Baluchistan in 1957-58 the uprising of Dad Shah, between 1968-75 the Baloch uprising supported by Iraq, developed. That uprising was the first coordinated action of the Baloch nationalists of Iran and Pakistan. Its leaders in exile in Baghdad formed the Baluchistan Liberation Front in 1963. Between 1968-75, their fighters confronted the units of the Iranian Army. After the government of Iraq with the Shah of Iran signed in 1975 the Alger Treaty, Tehran ceased the support of the Kurdish uprising in Iraq, and the Baghdad government ended the support of Baloch nationalists in Iran.

The province first was renamed to Baluchistan and Sistan, and afterwards Sistan and Baluchistan. Under the Pahlavi shahs, there was no education in Baloch language. Sistan and Baluchistan remained the most undeveloped province of Iran.

Sistan and Baluchistan and the Islamic Republic of Iran

Iran has roughly 1,6 million Baloch, comprising about 2 per cent of the total population. There are large Baloch population in Kerman Province as well.

In Sistan and Baluchistan Province there is the lowest life expectancy, adult literacy, primary school enrolment, access to improved water and sanitation, infant and child mortality. The province has the lowest income in Iran almost 80 per cent of the Baloch are living below the poverty limit. Contrary of the average of 65 per cent in the centre, the rate of literacy was 26 per cent in the province, where less than 5 per cent of the public servants were ethnic Baloch, where ethnic suppression was enshrined. The rate of unemployment is more than 50 per cent.

A significant segment of the population, the Baloch are Sunni Muslims, who are historically suffered from discrimination. Paradoxically, in the early 1980’s the Islamic Republic supported Sunni Islam to quell the growing secular and leftist sentiments of the Baloch. Now the province is full of Shia missionaries seeking to convert the local Sunni population.

In response, from the beginning of the 2000’s, Baloch militant groups emerged. The Jundullah (“The Army of God”), the Jaish Ul-‘Adl (“The Army of Justice”) and Harakat-e Ansar-e Iran (“The Glorious Movement of Iran”) groups are operating in Sistan and Baluchistan Province carrying out attacks against Iranian interests.

Jundullah is also known as Jonbesh-e Muqawamat-e Mardom-e Iran (“Iranian People’s Resistance Movement”), was founded in 2002 to protect the Baloch minority in Iran and started its armed struggle in 2005. The group comprises around 1,000 armed men. Jundullah recruits its fighters largely from Sunni seminaries and militants from the Rigi tribe. Jundullah is a decentralised militant group. Its strategy is to facilitate and train small groups already fighting the Iranian regime. The group attacked on then Iranian President Ahmadinejad’s motorcade in Baluchistan.

Its leader Abdul Malek Rigi and his deputy Abu Hamza were captured in February 2010 on board an aircraft flying from Kyrghizistan to Dubai by the Tehran government. After Rigi’s execution, Jundullah became more violent.

Jundullah does not intend to break away from Iran and to form a separate Baluchistan, its goal to enforce the respect of human rights, culture and faith of the Baloch people. After interacting with the banned radical Pakistani sectarian group, Lashkar-i Jangvi, Rigi adopted its anti-Iranian stance. Through this connection with Lashkar-i Jangvi Rigi went to Zabul Province of Afghanistan but the Afghan Taliban did not deal him for fear that he was connected to U.S. intelligence. In 2009 Rigi met with Al-Qaeda leaders in Turbat district of Pakistani Baluchistan and the Al-Qaeda agreed to support Rigi’s insurgency in Iran in return to facilitate in Iran from Pakistani Baluchistan.[3]

This transformation of Jundullah’s approach resulted the high-profile attacks during with General Noor Ali Sooshtari Deputy Head of Islamic Revolution Guards corps and Rajab Ali Mohammadzadeh, its provincial commander, were assassinated. Jundullah’s leader Maulawi Omar alleges that his group fights for religious and national rights of the Baloch.

In 2012 Jundullah renamed itself Sepah-e Rasulullah (“The Army of the Prophet of Allah”).

Jaish Ul-‘Adl is militant group. Some leaders who left Jundullah, established Jaish Ul-‘Adl. This group is pursuing some goals as Jundullah.

On October 15 2013 its fighters slaughtered fourteen Iranian border guards in Sarawan area. In November 2013 the group shot dead an Iranian prosecutor in Zahedan, facilitated a bomb attack in December 2013 where three Iranian revolutionary guards lost their lives. In February 2014 its fighters captured five Iranian border guards in the Jakigour area of Sistan and Baluchistan.

Harakat-e Ansar-e Iran has bounded its cause with wider Sunni and jihadist cause, created abroad, led by Abu Yasir Muskodani.

Iranian authorities accuse Baloch militant groups operating in Sistan and Baluchistan Province of being supported by the U.S., Britain, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia and by militant groups as the Taliban and Al-Qaeda. The Tehran government accused Washington of secretly funding ethnic groups in Iran to pressure Iran to give up its nuclear programme.

Afghanistan and Pakistan are grounds of proxy war between Saudi Arabia and Iran. While Saudi Arabia supported hard line Sunni groups as Lashkar-e Jangvi, Iran sided with Shiite militant groups as Sepah-i Muhammad. Saudi Arabia funded Sunni groups to create armed resistance in Iran. Saudi intelligence agencies were alleged being behind the abduction of sixteen Iranian police officers from Sarawan region in 2008. It is also rumoured that Jundullah operating from Pakistan. Abdul Malek Rigi was based in Pakistan and carried Pakistani national identity card in the name of Saeed Ahmed.[4]

Both Iran and Pakistan cooperated in the past in quelling Baloch nationalist movements and have important economic ties. In February 2014 the governments of Tehran and Islamabad signed a pact sharing responsibility for combating drug traffickers and militants operating across the border and facilitating easier to extradite prisoners. On April 6, 2014 the Iranian parliament passed a bill that paves the way for the Iranian and Pakistani governments to enhance security cooperation.

The Iranian security forces fired a large number of rockets from the Iranian side on the border towns of Panjgur and Mashkil in Pakistani Baluchistan. In 2013 and 2014 the firing of mortars across the border and incursions of Iranian military personnel and violation of Pakistani airspace by Iranian helicopters were reported. Baloch nationalist groups alleged that Tehran is carrying out such operations inside Baluchistan with the support of the Islamabad government as a continuation of their longstanding anti-Baloch operations in the past.

In addition to Iran’s rivalries with the U.S. and Saudi Arabia led Gulf Arab monarchies and the crippling effects on long time economic sanctions imposed on Iran due to its nuclear programme, the resurgence of a Baloch insurgency can strongly impact Iran’s stability and hence that of the entire region. The Iranian Baloch militant groups are a good example how militant groups are exploiting the complicated relations among competing regional states. Furthermore, sectarian violence is an unpredictable menace in Pakistan to increase sectarian tensions in bilateral relations.

Iran is also afraid of the threat of Baloch insurgency poses to its territorial integrity and regional stability. The Tehran government deployed additional security and military units to Sistan and Baluchistan, regularly holds military exercises, coordinates their activities with IRGC, and tightens control of the border, neglects the 1956 agreement of free passage within 60 km depth, constructs wall on the border.

But the grievances of the Baloch are cultural, economic, social, ethnic, and cannot be solved by military force alone. Instead, what is needed is a fair distribution of resources and the intense development of public infrastructure, creating jobs, greater Baloch participation is social affairs.

However, instability in Iran’s Sistan and Baluchistan Province penetrated by Baloch insurgent groups can scare away potential investors of a delayed Iran-Pakistan pipeline project and can prevent its construction. The free trade port of Chahbahar actually being used as a platform for the transit of goods to Afghanistan and Central Asian markets, have injected some economic life in the region. The central government should expand the province’s transit capacities to benefit from the growing wealth and commercial activities in Central Asian markets. Furthermore, the construction of the Iran-Pakistan pipeline can has generated an economic momentum and could further empower the region to invest in gas-based industries. Caught between armed smuggling and armed insurgency and plagued by underdevelopment, unemployment, and poverty, the province is in dire need of attention of the central government.

References:

[1] HOSSEINBOR, Mohammad Hassan: Iran and Its Nationalities: The Case of Baloch Nationalism, American University Beirut, 1984, 153. P.

[2] HARRISON, Selig: In Afghanistan’s Shadow: Baloch Nationalism and Soviet Temptations, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, New York: 1981, 12.p.

[3] SHEHZAD, Syed Saleem: Inside Al-Qaeda and the Taliban: Beyond Bin Laden and 9/11, London: Pluto Press, 2011

[4] ZIA UR-RAHMAN: The Baluch Insurgency: Linking Iran to Pakistan, NOREF (Norvegian Peacebuilding Resource Centre Report, May 2014, https://www.cionet.org/attachments/25296/uploads, Retrieved: 22.07.2016

Dr. Katona was born in Budapest, Hungary. A Member of the Commission of Military Sciences, C.Sc., she has served in various diplomatic posts in Afghanistan and the region. Now she is a Research Fellow at the Strategic Center for International Relations and a member of the Editorial Board of its quarterly publication.

The Afghan Tribune | Dr. Nasrin Katona | Published: August 02, 2016, 04:07 PM

No comments:

Post a Comment