Inherently Unstable?

Pakistan has always been a

somewhat unstable state; one might even argue it was

built upon not just a myth but a falsehood. Even before

they created Pakistan, the Muslims of the subcontinent

have been divided and confused about many basic

questions defining the nation and the state.1 The

original conception, as Stephen Cohen of the Brookings

Institution has explained, was for a Pakistan as an

“extraordinary” state, “a homeland for Indian Muslims

and an ideological and political leader of the Islamic

world.”2 At the same time, the ideology of the Pakistan

movement was opaque and contradictory, with the

contradictions seemingly captured in the figure of

its leader, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Karachi-born but

trained as a lawyer in England and retaining a lifelong

affinity for fine English tailoring. Though a partner of

350

Gandhi and Nehru in the Indian Congress, Jinnah was

suspicious of their all-India approach, and as British

imperial power on the subcontinent began to wane in

the early 20th century, the compact between Indian

Hindu and Muslim likewise weakened. Moreover,

Kemal Ataturk’s abolition of the Ottoman caliphate in

1922 threw the Muslim world into turmoil, with the

particular effect of politics becoming ever more local;

the pan-Islamic caliphate movement collapsed entirely.

There was rising political uncertainty not only in the

subcontinent but across the broad Islamic world.

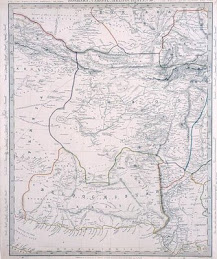

Thus, at the 1928 session of the Indian Congress,

Jinnah proposed not only guaranteed seats for Indian

Muslims in national and provincial legislatures,

but the creation of three “designated Islamic

states”─Sind, Baluchistan, and the Northwest Frontier

Province─within a future independent Indian

federation. In other words, while the subcontinent

was still struggling to separate itself from British rule,

Jinnah was proposing an ethnic state-within-a-state

that held within it the promise of further separation.

To be sure, to Jinnah and others, the allegedly inclusive

All-India Congress appeared more like a vehicle for

Hindu political dominance. And the definition of who

was a “Muslim” was mostly defined in distinction to

Hinduism and elided traditional differences between

regions and tribes. The deeply secular Jinnah declared

in 1940 that the two communities “are not religious in

the strict sense of the word, but are in fact different and

distinct social orders. And it is a dream that the Hindus

and Muslims can ever evolve a common nationality.”3

Jinnah’s dream also held an expansionist tendency.

When Gandhi embarked upon his “Quit India”

campaign at the nadir of Britain’s fortunes in World

War II, Jinnah seized the opportunity to double his

351

territorial demands, adding Kashmir, the Punjab, and

Bengal to his list of Muslim provinces. Though this

would prove to be an inherently unstable strategic

fantasy, Britain, in its haste to leave India after the

war, allowed the growing fissures between Hindu

and Muslim to fester. In the final solution to the Raj,

the Punjab and Bengal were split, inciting massive

ethnic cleansing and resulting in the deaths of nearly

1 million people and, of course, leaving Kashmir a

contested province. The fundamental instability of

the new Pakistan was apparent from the start, and

was confirmed─though hardly entirely resolved─by

the 1971 secession of East Pakistan. That the nascent

“Bangladesh” would rely on Hindu India to secure

the separation, showed the weakness of Jinnah’s and

Pakistan’s ideas of Muslim brotherhood. The bond of

Islam was not strong enough to convince Bengalis that

they should remain confederate with, and subordinate

to, Punjabis.

“Pakistan is a paranoid state,” writes Stephen

Cohen, “that has enemies.” Pakistani strategists

and political elites fear they may become a “West

Bangladesh─a state denuded of its military power,

and politically as well as economically subordinated

to a hegemonic India.”4 Yet, somewhat perversely,

the result is a strategic “adventurism,” by which

Cohen means Pakistan’s ambitions in Kashmir and

Afghanistan, but which should be applied equally to

Pakistan’s nuclear program, its relations with China,

and its ambiguous stance vis-à-vis the Taliban, al-

Qaeda, various “associated movements” internationally,

and its homegrown radicals. Indeed, it is hard to escape

the conclusion that Pakistan began as and remains

a profoundly unsettled and unsettling political

phenomenon, both internally and internationally.

352

Curiously for a self-conceived Islamic state, Pakistan

has found it difficult to deal with a narrower but more

immediately powerful vision of Islam─that advanced

by al-Qaeda and the radicals. Islamist madrassas have

provided education and other state services when

and where the Pakistani government has not. The

Pakistani army, by far the strongest institution of the

state, has long had cozy relations with Islamist groups,

particularly in the eternally troublesome North-West

Frontier Province. The traditional wisdom is that the

army holds the upper hand. Cohen expresses this

perfectly. “The political dominance and institutional

integrity of the Pakistani [army] remain the chief

reasons for the marginality of radical Islamic groups,”

he concluded even in 2003. “Although the army has a

long history of using radical and violent Islamists for

political purposes, it has little interest in supporting

their larger agenda of turning Pakistan into a more

comprehensively Islamic state.”5

But who is using whom is difficult to tell from a

distance. At a minimum, there seems to be a strong

correlation of interests between Islamic radicalism

and Pakistan’s otherwise “national” interests, or the

interests of Pakistan’s Pashtuns. Indeed, the history of

Pakistan is─to oversimplify for the sake of clarity─a

history of the pact between Punjabis and Pashtuns,

a partnership reflected particularly through the

Paksitani army and officer corps. While this has itself

been an unstable relationship, it has helped keep a lid

on the even more fissiparous tendencies of Sindhis

and Baluchis. It has also made the Punjabis partners

in the nationalistic yearnings of Pashtuns to reclaim

“Pashtunistan”─a homeland cut in half by the 1893

Durand Line, the border that allegedly advanced

British colonial interests but, like a good number of

353

the borders throughout the Islamic world, left constant

conflict in its wake.

This has made for unending border wars, both in

Kashmir─it was Pashtun tribesmen, supported by the

Pakistani army, who sparked the fighting that began

in October 1947, shortly after the British withdrawal,

and continues to this day─and in Afghanistan. The

persistence of terror and guerilla attacks in Kashmir,

such as the recent series of bombings in Srinagar, is

in part a product of “tolerance” in Islamabad, as is

the continuing tension with Afghanistan. Speaking

at a counterterrorism conference in Turkey in March,

Afghan President Hamid Karzai─a Pashtun himself,

it should be remembered─complained that extremist

tendencies and terrorism in Afghanistan were not just

an internal problem, but the result of “political agendas

and the pursuit of narrow interests by governments.”

By this euphemism, Karzai meant Pakistan, as he

made clear when talking about the Taliban, whose

rise in the 1990s he described as a “hidden invasion

propped up by outside interference and intended to

tarnish the national identity and historical heritage” of

Afghanistan.6

Yet it would be a mistake to blame all of Pakistan’s

internal and border problems on the Pashtuns; Punjabis

have often been at odds with their Baluchi and Sindhi

countrymen. Recent deployments of the Pakistani

army to Karachi, ostensibly to dampen unrest in the

wake of a suicide attack that killed three Sunni Muslim

clerics but seen to be a move against the large Baluchi

population there, have fueled Baluchi separatist

feelings. Islamabad “has treated Baluchistan like a

colony,” complained Imran Khan, a member of the

Pakistani parliament. Baluchi nationalist Humayun

Baluch charges that Punajbis are being introduced as

354

settlers, traders, and miners. “[Our] provincial resources

are being exploited and looted,” he says. “People’s

rights are being compromised and everything is being

done for the benefit of the Punjabis. Army troops, army

weaponry, helicopters, jets, and F-16s are being used

in Baluchistan. The population is being forced out and

primarily living in Sindh [in Karachi]. Houses have

been burned and looted.”7

Also irritating to Baluchi national pride is the

construction of the Gwadar port and the influx of

Chinese engineers who oversee the project. On May 3,

2004, the “Baluchistan Liberation Army” killed three

Chinese engineers working on the port project, an

effort that employs several hundred Chinese nationals.

Baluchi nationalists believe that Beijing is in league

with Islamabad to develop and export the province’s

natural gas resources. Pakistan’s leading natural gas

company, Sui, is located in Baluchistan but provides

products for the entire country.

Pakistan was born in instability and retains a

political culture marked by deep insecurity and

uncertainties that underlie the idea of the Pakistani

nation and the formation and history of the state of

Pakistan. These distortions are exacerbated by the

army’s dominance of the state; civil society has been

unable to soothe either Pakistan’s real fears or the fears

that are the unsurprising result of “adventurism.” Even

those accustomed to Pakistan’s “normal” instability,

like Stephen Cohen, cannot be sure that the army will

continue to balance these many competing demands

in the face of rising Islamic populism or Baluchi

separatism; he is not confident much beyond the

immediate future. The more Pakistan acts as though

it were cornered, the more cornered it becomes. The

more tightly the army grips the reins of power, the

more likely the bridle may break.

m.sarjov

Type: Book

Pakistan's Nuclear Future: Worries Beyond War. Edited by Mr. Henry D. Sokolski.

Tuesday, May 6, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

You might be interested in Henry Kissinger's new domino theory about Iraq and radical Islam in India. On the FaithWorld blog at http://blogs.reuters.com/faithworld/2008/05/27/kissinger-iraq-and-indias-muslims-a-new-domino-theory/

Post a Comment