Tuesday, July 28, 2009

Inside Kalat

Inside Kalat

Reviewed by Farhan Siddiqi Sunday, 31 May, 2009 03:58 PM PST

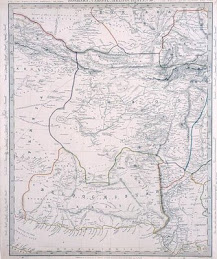

NOT two, rather three political units proclaimed independence in the middle of August 1947: Pakistan on August 14, India and the Khanate of Kalat on August 15. By virtue of Kalat’s independence, Pakistan became a unique state in more ways than one.

Firstly, Pakistan’s geographical discontiguity as expressed in the 1,000 mile separation of its two wings made the new state an aberration. Modern nation-states are defined by their territorial contiguity while Pakistan’s geography was contrary to the established norm.

Secondly, the independence of Kalat meant that there was a state within a state in Pakistan. Both geographical facts presented important challenges. One eventually separated to form a state of its own (Bangladesh) while the other geographical unit (Kalat) saw the rise of an intense and radical nationalist movement which up to the present time has defied an amicable solution.

Why did a nationalist movement emerge in Balochistan and how did the Khanate of Kalat become the centre of nationalist activities? Theoretically, Axmann’s understanding of nationalism is firmly rooted in a modernist framework which belies the argument that ethnic identities are innate.

Baloch nationalism was ‘constructed’ and ‘created’ by Baloch leaders, and it only took shape in the years 1915 till 1955 in response to political circumstances prevailing at the time. It was concretised as a result of the development of a political party, the Anjuman-i-Ittehad-i-Balochan-wa-Balochistan in 1930-31 led by two nationalist stalwarts, Mir Yusuf Ali Magsi and Abdul Aziz Kurd.

The Anjuman gained further credence in the agency and personality of Mir Ahmad Yar Khan who became the Khan of Kalat in 1933. With active support from the Khan, the Anjuman spread its activities and eventually transformed itself as the Kalat State National Party (KSNP) in 1937 which now included within its fold eminent personalities such as Ghous Bux Bizenjo and Mir Gul Khan Naseer. Interestingly, at the same time that the Khan was supportive of and sympathetic to Baloch nationalists, he was also cognizant of protecting and preserving his own power base leading him to a collision course with the nationalists. Mir Ahmad Yar declared the KSNP illegal in July 1939.

With high empirical research the author traces through primary documents, including Kalat’s declaration of independence. This came about after a Standstill Agreement was signed between the future state of Pakistan, the British and the Khan of Kalat on August 4, 1947.

Axmann points out the anomaly of the Agreement with respect to Articles I and IV. While Article I attested to the fact that ‘Kalat was an independent state, quite different in status from other states in India’, Article IV contradictorily stated that ‘Pakistan shall be the legal, constitutional and political successor of the British’. This meant that Pakistan never agreed to the independence of Kalat and as soon as the British left, Jinnah demanded that the Khanate be merged with Pakistan and annul its independent status.

It is indeed startling that Jinnah being the legal advisor to the Khan of Kalat had presented a case for Kalat’s independence before the Cabinet Mission in 1946.

For the rest of Balochistan and the Marri and Bugti tribal areas, a referendum was held. The author is quite candid and agrees with the views of Baloch nationalists that a referendum never actually took place, rather the meeting of the Shahi Jirga broke up over disagreements and within the ensuing confusion it was suddenly announced that Balochistan had decided to join Pakistan.

Kalat’s independence was ultimately revoked in March 1948 when the Khan signed the Instrument of Accession. The merger led to the germination of the first Baloch resistance in the post-colonial period led by Abdul Karim, younger sibling of the Khan of Kalat.

One theme which the author does not allude to in his analysis of Baloch nationalism is the fact that nationalism despite being a product of modernity is not necessarily and functionally dependent on it. Nationalism may erupt in the most, as well as, least modernised socio-political contexts. Balochistan is a classical example of the latter while Basques in Spain and Northern Ireland in the United Kingdom are striking examples of the former.

Although the author has tried to prove that Balochistan was affected by modernity leading the Baloch to clamour to nationalist identity as a basis of their politics, the analysis is at best faulty. Balochistan was unaffected by the currents of modernity proving that nationalism is best understood as an ideology and political movement rather than a functional pre-requisite of modernity, which political elites have instrumentalised in face of authoritarian political structures bent on denying them their identity and existence.

The book which is highly informative represents detailed research of primary documents. Its main strength lies in its empirical setting.

Moreover, Axmann places partisan Pakistani scholarship on Baloch nationalism and contrasts it with works by Baloch nationalists presenting an interesting and comparative analysis of how political developments are viewed by scholars on different sides of the divide.

The book is a must read for all those interested in understanding the rise of Baloch nationalism in the colonial and post-colonial period.

Back to the Future: The Khanate of Kalat and the genesis of Baloch nationalism (1915-1955).http://www.dawn.com/wps/wcm/connect/dawn-content-library/dawn/news/pakistan/provinces/03-inside-kalat-ss-05

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment