|

March 7, 2011

“Blame it on the English” is a popular Lebanese wisecrack; the idiot savant’s elixir and the learned man’s exit line when answers become too few and far between. “When all else fails, blame it on the English!” goes the playful adage. Yet, when placed in a wider Middle Eastern context the phrase loses its flippancy and reveals a remarkably keen grasp of history.

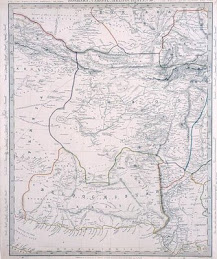

“Blame it on the English” is a popular Lebanese wisecrack; the idiot savant’s elixir and the learned man’s exit line when answers become too few and far between. “When all else fails, blame it on the English!” goes the playful adage. Yet, when placed in a wider Middle Eastern context the phrase loses its flippancy and reveals a remarkably keen grasp of history.After all, the British—or rather the English in Middle Eastern parlance—did probably get most things wrong about the region, and are perhaps fair game for the blame. The checkered Eastern holdings of the Ottoman Empire, which they inherited alongside the French in 1918, were viewed by the British as a homogenous exclusive preserve of Muslims and Arabs; a “land-bridge” as it were to His Majesty’s crown jewel, India. And so it behooved the British and their colonial cartographers to maintain, or rather to contrive, a single monolithic “Arab world,” in what is to this day an inherently diverse, fractured, and fractious Middle East.

The French on the other hand, partly to spite their British rivals and scuttle their colonial designs—in favor of a loftier Gallic mission civilisatrice—viewed things differently. Pursuing more than the facile “divide and conquer” colonial strategy often attributed to them by classic post-colonialists, the French were avid practitioners of a "minorities policy.” With antecedents in Northern Africa (the Berbers) and the Levant region (Lebanon and the Maronites) the French perceived the Middle East for the ethno-religious and linguistic mosaic that it really was. Robert de Caix, secretary to the French High Commissioner in Beirut, wrote in a November 1920 diplomatic telegram to the Quai d’Orsay that:

The entire Middle East has been so poorly packed together [by the British.] The resulting clutter is all the more legitimate reason for [the French] to try and steer the minds clear of unitary political systems and, instead, advance federalist concepts […] Federalism would be a great relief for much of the notables of these lands, and a boon to the bulk of this region’s populations, who remain, to a very large extent, alien to all kinds of [unitary] political life.1Indeed, terms and concepts such as the “Arab world” and the “Arab nation” are modern twentieth century innovations owed in no small part to British colonial genius, not to any distinctly “Arab” group loyalty. History—and certainly “Arab” and Muslim history—makes no mention of a united “Arab world” or a cohesive “Arab nation” antecedent to the modern Middle Eastern state system. Even inhabitants of the Arabian Peninsula, prior to the seventh century Muslim conquest of the Levant and the Fertile Crescent, were never a coherent cohesive lot with a unified corporate identity and a single national language. Instead, pre-Islamic Arabians were at best a menagerie of warring tribes, vying city-states, and rival families and clans using a multiplicity of idioms and languages that bore little resemblance to what later became the language of Quran, and what is today referred to as “Modern Standard Arabic.” Of course there is much truth to the belief that the Prophet Muhammad, the founder of Islam, had united those fickle and inchoate Arabians into a single nation—or Umma. But the resulting Umma was a Muslim, not an Arab nation, and the regions it came to hold in its grip—from Spain to the Indus—continued to be characterized by large swaths of local, indigenous, non-Muslims, and non-Arab ethnic and cultural communities.

This is the Middle East that the French and British inherited in the early twentieth century; a mosaic of ethnic and religious groups that certainly included Arabs, but which was far from being exclusively Arab. De Caix, and by inference the French Foreign Ministry and the League of Nations Mandatory Authorities that he represented, were acutely aware of this ethnic and cultural mosaic. That was one of the main reasons the French turned their Mandatory possessions into five distinct, ethnically coherent, and largely homogenous non-Arab states: The State of Greater Lebanon, the State of Damascus, the State of Aleppo, the Alawite Mountain, and the Druze Mountain. Had the British not dismantled these new creations in 1936, in favor of an artificially united Syria (or a unitary Iraq or Jordan for that matter,) arguably sounder and less fractious entities could have emerged and survived into our times; states that might have remained at peace with themselves and their neighbors.

To this day, with the future of a post-Mubarak Middle East still up in the air, in a region still facing more pivotal changes than the prevalent analyses and projections are willing to entertain, a Christian dominated “Mount Lebanon," an Alawite dominated “Mount Ansariyya," and a Druze dominated “Druze Mountain”—as the French had envisioned in 1920—might still make more political, ethnic, and historical sense than the current restive, and still unraveling, Arab nationalist order.

Modern-day Syria became the unitary state that it represents today through British machinations, not by the will and writ of the French Mandatory power, and certainly not in response to the desires of its disparate constitutive elements. But by 1940 France had ceased being the great power that it had once been: Vichy had fallen to the Nazis, and the role of the “Free-French” was relegated to military marginality and political subservience to the British. In the Levant, Britain was now calling the shots and a united “Arab world” resurfaced as its lodestar, even as many of the region’s inhabitants, namely Alawites, Christians, Shi’ites and Druze, remained opposed to the concept. And this opposition stemmed from a long pedigree.

In a November 1, 1923, issue of the monthly El-Alevy (The Alawite), an open letter to French académicien and legislator Maurice Barrès summed up the Alawites’ desiderata of the time, which to this day, although arguably in occultation, remain largely unchanged:

It is with immense gratitude that we applaud your unfailing defense and advocacy on behalf of our nascent Alawite State; a young State which some seek, unjustly, to attach to a future Syrian Federation, oblivious to the will of the overwhelming majority of our people […] We urge you to take all measures necessary to safeguard our continued and complete autonomy, under the auspices of French protection, and kindly accept our heartfelt appreciation and warmest thanks.2This attitude was validated and reconfirmed some fifteen years later, through a written appeal signed by Suleiman al-Assad no less, the grandfather of Bashar al-Assad, the current Alawite ruler of Syria. In this 1936 letter the elder Assad implores French authorities to protect the freedom and independence of the Alawite people, guarantee their safety against the “spirit of hatred and fanaticism embedded in the hearts of the Arab Muslims,” and prevent the fusion of the State of the Alawite Mountains into any future Syrian union.3

Still, British designs prevailed, and new, unitary, Arab-defined creations emerged—bereft of historical precedents and legitimate political bases. Today the foundations of this “Arab” edifice are being shaken, and new states—perhaps even new nations—are beginning to take shape, arguably redeeming the early twentieth century French. What does the future hold for Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Syria, and the rest? Could it be that Arabism as the sole, overarching parameter of selfhood has run its course? Is it a spent force in a Middle East intent on slaying its Arab nationalist heroes of yore; its Qaddafis, Mubaraks, and others?

Clearly, and despite many claims to the contrary, the dismantlement of the anciens régimes of Egypt, Tunisia, and Libya point to a defrocking of the Arab nationalist order, not its “rebirth”; it signals the emergence of new nation-states, not the mending of an old ideology. Much has been written of late about the region’s turmoil bearing the markings of Eastern-Europe-1989. The comparison is tempting. However, it is not unlikely that future historians might revise this parallel and re-christen this year’s momentous events as the early stirrings of a Middle Eastern “Peace of Westphalia”; the breakup of the imperial Arab order and the birth of new free nations. Eastern-Europe-1989 did not only bring about the fall of the Iron Curtain; it raised a Velvet Curtain to reveal the birthing of new nations. Not Egypt, not Libya, and not Tunisia; Sudan is the glimpse into the future of the Middle East. In 2003 former Iraqi dissident, Kanan Makiya, wrote that the new Iraqi state he yearned for had to be federal and non-Arab in order for it to be viable.4 Makiya’s candor angered many Arabist romantics. Yet his remains the only peaceful formula for the mosaic of cultures, languages, and ethnicities that is the Middle East; the best last chance for the region’s “Peace of Westphalia” to pan out; otherwise a Muslim “Thirty Years War” is very likely to be in the offing.

1 See French Foreign Ministry Archives (Archives du Ministère des affaires étrangères), Correspondence Politique et Commerciale, Serie “E”, Levant-1918-1940, Sous-Série: Syrie, Liban, Cilicie, Carton 313, dossier 27, pp. 39-40.

2 French Foreign Ministry Archives (Archives du Ministère des affaires étrangères), Levant 1918-1929, Syrie-Liban, Vol. 290-292, Carton 417, Dossier 1, “The Alawites Thank Maurice Barrès”, El-Alevy, Novermber 1, 1923, Vol. 1, No. 1, page 4.

3 French Foreign Ministry Archives (Archives du Ministère des affaires étrangères), Levant 1918-1940, Syrie-Liban, Vol. 700, Carton 354, Dossier 7.

4Kanan Makiya, ”A Model for Post-Saddam Iraq”, The Journal of Democracy, Vol. 14, No. 3, July 2003, pp. 9-10.

http://nationalinterest.org/commentary/the-arab-westphalia-4949

No comments:

Post a Comment