IN April 2015, Pakistani entrepreneur, arts patron

and human rights campaigner Sabeen Mahmud was shot dead by unknown

assailants. The 40-year-old was leaving an event titled ‘Unsilencing

Balochistan’ that she had organised at her Karachi arts space T2F. Since

then, evidence has come out in the press indicating that the killing

probably had nothing to do with the T2F seminar on Balochistan.

Nevertheless, even the security establishment was never in favour of

this seminar — which was earlier to be hosted by Lahore University of

Management Sciences — being held.

At this point it seems important to learn about Balochistan, its literary representation, and why the province needs ‘unsilencing’.

Let us start by examining the Raj period. In one of Rudyard Kipling’s least impressive poems, ‘The Story of Uriah’, the British attitude towards Balochistan is sketched. The poem centres on a hapless colonial administrator, Jack Barrett, whose superior officer banishes him to what is sarcastically described as “that very healthy post” of Quetta. The officer was having an affair with Jack’s wife in the verdant hill station of Simla and wanted him out of the way. Within a month of his enforced transfer Jack died and his body was interred in a “Quetta graveyard”. The poem suggests that colonisers saw the important strategic base of Quetta as a remote, backward, disease-ridden outpost.

There is scant more affection for the hilly landscape around Quetta in Bertram Mitford’s The Ruby Sword. Subtitled A Romance of Baluchistan, this is a fin-de-siècle colonial adventure story by a scion of the aristocratic Mitford family. Howard Campian is on his first visit to the region. He finds it bleak, lacking in vegetation, and occasionally flood-prone. This portrayal chimes with intrepid British travel writer Harry de Windt’s 1891 book A Ride to India Across Persia and Baluchistàn, in which he claims that it is a “standing joke” that Balochistan only contains one single tree.

Mitford’s novel is really about the rekindling of Campian’s love affair with his ex-fiancée Vivien Wynier. This is pinned on to a preposterous plotline of the quest for a precious sword lost in Balochistan decades earlier. Unlikeable British characters are condemned for their overtly racist language and sanctioning of unprovoked violence against what they call the “hill tribes”. Yet even the more sympathetic British characters, Campian and his host John Upward, view the Baloch’s “religious fanaticism” and “utterly fearless, utterly reckless” nature as pathological. This view accords with Sir George MacMunn’s 1933 work The Martial Races Of India, in which he lumps the Baloch together with Pakhtuns as having “sporting, high-spirited, adventurous” personalities.

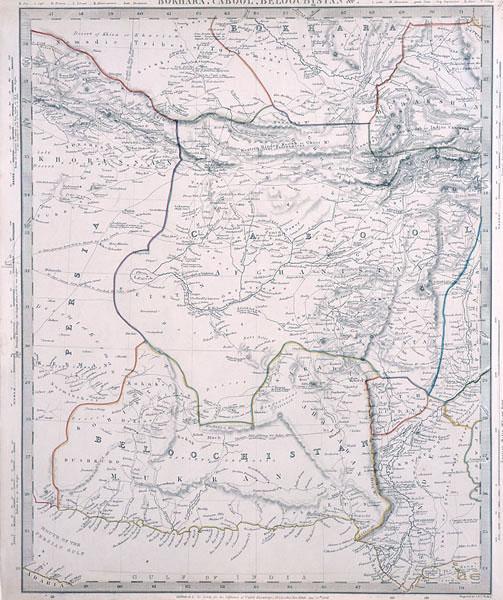

Asked to explain Balochistan’s situation to British friends who know little about it, I use two analogies. The first compares the Baloch’s tripartite scattering between Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Iran with that of their relations, the Kurds, between Iran, Iraq, and Turkey. Another inexact parallel is between Balochistan and Bangladesh. Both regions were subsumed under the Pakistani nation-state following the 1947 Partition, but each had proudly distinct cultural heritage, language, and loyalties. Whereas India eventually threw its weight behind the Bangladesh ‘War of Liberation’ in 1971, the Baloch’s 1970s nationalist struggle did not meet with the same support or success. According to Justin S. Dunne, the bloody insurgency that lasted between 1974 and 1977 caused the deaths of approximately 5,300 ethnic Baloch and 3,000 Pakistani military personnel.

It is the 1960s and 1970s struggles in the western borderlands that the Punjabi writer Jamil Ahmad examines in The Wandering Falcon, which was completed in 1973. The book wasn’t published for almost three decades, by which time the region was again roiled by state violence against separatists. From a Baloch perspective Ahmad might appear just as much of an interloper as those earlier British authors Kipling, Mitford, and de Windt. Yet because he worked for many years as a civil servant in the western borderlands and the Northern Areas, his fiction has insight and texture. For example, Ahmad’s characters convey a different view of the topography than the three Britons’ impressions of dull monotony:

“...[T]he land — their land — had seen to it that beauty and colour were not erased completely from their lives. It offered them a thousand shades of grey and brown with which it tinted its hills, its sands and its earth … To the men, beauty and colour were rampant around them.”

The local people’s trained eyes are able to discern far more than 50 shades of grey in the parched landscape. In stories such as ‘The Sins of the Mother’, ‘A Point of Honour’, and ‘The Death of Camels’, Ahmad portrays the Siahpad Tribal Area, an honour killing, and the cross Af-Pak routes of the nomadic Kharoti tribe. He conveys without judgement the Balochis’ macho factionalism, their harsh jirga punishments, and strong sense of honour and hospitality.

In her field-defining book Resistance Literature (1987), US academic Barbara Harlow includes a short discussion of Balochistan amidst exploration of the Palestinian, Sandinista, Mau Mau, and other liberation struggles. Through readings of poems by Balach Khan, Harlow perceives “a sadness engendered by an ongoing struggle, a struggle not yet consummated”.

She argues in favour of the Baloch’s right to territorial self-determination. But Balochistan is no Palestine; it has little experience of self-governance. What is more, unlike the Bengalis and Kurds, there isn’t an established Baloch middle class or history of political activity. In 2011, Anatol Lieven averred that independence would only bring “a Somali-style nightmare, in which a range of tribal parties … under rival warlords would fight for power and wealth”. A solution might be found between Harlow’s resistance and Lieven’s pro-army stance. The creation of an autonomous Balochistan might go some way towards assuaging the Baloch’s grievances.

These complaints focus on unequal distribution of the region’s rich resources, of gold, copper, zinc, oil, and natural gas, and the divisive Sino-Pakistani development of the deep sea port of Gwadar. Balochistan is easily Pakistan’s largest province, but it has the least numerous, poorest, and most uneducated population.

Since 2005, following an uprising sparked by the rape of a female doctor in Dera Bugti district, nationalists have been subjected to enforced disappearances. Sometimes they are released but have been so badly tortured and threatened that they are silenced. However, increasingly, nationalists are being murdered and their bodies dumped in public places, allegedly often by Pakistan’s intelligence agencies.

In 2013 Pakistani novelist and journalist Mohammed Hanif wrote a short, generically-indeterminate book for the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan. He conducted interviews with relatives of the disappeared and wove them into the succinct, hard-hitting stories of The Baloch Who Is Not Missing and Others Who Are. From the father who is overwhelmed by paperwork when his son disappears, to the sister who puts her personal life on hold as she protests for her brother’s release, voices tell of the Kafkaesque bureaucracy and callous authorities these families are up against.

Although Balochistan was a popular setting for colonial writers such as Kipling and Mitford, until recently Baloch were missing from Pakistani literature in English. In the 1970s, Ahmad made the bleak observation that the dead of Balochistan “will live in no songs; no memorials will be raised to them”. This is starting to change. Although the songs are currently being sung by only a few weak voices and the memorials are makeshift and puny, they nonetheless create an impact. An increasing number of writers are turning their attention to this war-torn nation. Perhaps more will join their ranks in the wake of littérateuse Mahmud’s tragic murder.

CLAIRE CHAMBERS teaches global literature at the University of York and is the author of the forthcoming book Britain Through Muslim Eyes: Literary Representations, 1780-1988.

http://www.dawn.com/news/1189376/column-the-baloch-who-is-missing

At this point it seems important to learn about Balochistan, its literary representation, and why the province needs ‘unsilencing’.

Let us start by examining the Raj period. In one of Rudyard Kipling’s least impressive poems, ‘The Story of Uriah’, the British attitude towards Balochistan is sketched. The poem centres on a hapless colonial administrator, Jack Barrett, whose superior officer banishes him to what is sarcastically described as “that very healthy post” of Quetta. The officer was having an affair with Jack’s wife in the verdant hill station of Simla and wanted him out of the way. Within a month of his enforced transfer Jack died and his body was interred in a “Quetta graveyard”. The poem suggests that colonisers saw the important strategic base of Quetta as a remote, backward, disease-ridden outpost.

There is scant more affection for the hilly landscape around Quetta in Bertram Mitford’s The Ruby Sword. Subtitled A Romance of Baluchistan, this is a fin-de-siècle colonial adventure story by a scion of the aristocratic Mitford family. Howard Campian is on his first visit to the region. He finds it bleak, lacking in vegetation, and occasionally flood-prone. This portrayal chimes with intrepid British travel writer Harry de Windt’s 1891 book A Ride to India Across Persia and Baluchistàn, in which he claims that it is a “standing joke” that Balochistan only contains one single tree.

Mitford’s novel is really about the rekindling of Campian’s love affair with his ex-fiancée Vivien Wynier. This is pinned on to a preposterous plotline of the quest for a precious sword lost in Balochistan decades earlier. Unlikeable British characters are condemned for their overtly racist language and sanctioning of unprovoked violence against what they call the “hill tribes”. Yet even the more sympathetic British characters, Campian and his host John Upward, view the Baloch’s “religious fanaticism” and “utterly fearless, utterly reckless” nature as pathological. This view accords with Sir George MacMunn’s 1933 work The Martial Races Of India, in which he lumps the Baloch together with Pakhtuns as having “sporting, high-spirited, adventurous” personalities.

Asked to explain Balochistan’s situation to British friends who know little about it, I use two analogies. The first compares the Baloch’s tripartite scattering between Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Iran with that of their relations, the Kurds, between Iran, Iraq, and Turkey. Another inexact parallel is between Balochistan and Bangladesh. Both regions were subsumed under the Pakistani nation-state following the 1947 Partition, but each had proudly distinct cultural heritage, language, and loyalties. Whereas India eventually threw its weight behind the Bangladesh ‘War of Liberation’ in 1971, the Baloch’s 1970s nationalist struggle did not meet with the same support or success. According to Justin S. Dunne, the bloody insurgency that lasted between 1974 and 1977 caused the deaths of approximately 5,300 ethnic Baloch and 3,000 Pakistani military personnel.

It is the 1960s and 1970s struggles in the western borderlands that the Punjabi writer Jamil Ahmad examines in The Wandering Falcon, which was completed in 1973. The book wasn’t published for almost three decades, by which time the region was again roiled by state violence against separatists. From a Baloch perspective Ahmad might appear just as much of an interloper as those earlier British authors Kipling, Mitford, and de Windt. Yet because he worked for many years as a civil servant in the western borderlands and the Northern Areas, his fiction has insight and texture. For example, Ahmad’s characters convey a different view of the topography than the three Britons’ impressions of dull monotony:

“...[T]he land — their land — had seen to it that beauty and colour were not erased completely from their lives. It offered them a thousand shades of grey and brown with which it tinted its hills, its sands and its earth … To the men, beauty and colour were rampant around them.”

The local people’s trained eyes are able to discern far more than 50 shades of grey in the parched landscape. In stories such as ‘The Sins of the Mother’, ‘A Point of Honour’, and ‘The Death of Camels’, Ahmad portrays the Siahpad Tribal Area, an honour killing, and the cross Af-Pak routes of the nomadic Kharoti tribe. He conveys without judgement the Balochis’ macho factionalism, their harsh jirga punishments, and strong sense of honour and hospitality.

In her field-defining book Resistance Literature (1987), US academic Barbara Harlow includes a short discussion of Balochistan amidst exploration of the Palestinian, Sandinista, Mau Mau, and other liberation struggles. Through readings of poems by Balach Khan, Harlow perceives “a sadness engendered by an ongoing struggle, a struggle not yet consummated”.

She argues in favour of the Baloch’s right to territorial self-determination. But Balochistan is no Palestine; it has little experience of self-governance. What is more, unlike the Bengalis and Kurds, there isn’t an established Baloch middle class or history of political activity. In 2011, Anatol Lieven averred that independence would only bring “a Somali-style nightmare, in which a range of tribal parties … under rival warlords would fight for power and wealth”. A solution might be found between Harlow’s resistance and Lieven’s pro-army stance. The creation of an autonomous Balochistan might go some way towards assuaging the Baloch’s grievances.

These complaints focus on unequal distribution of the region’s rich resources, of gold, copper, zinc, oil, and natural gas, and the divisive Sino-Pakistani development of the deep sea port of Gwadar. Balochistan is easily Pakistan’s largest province, but it has the least numerous, poorest, and most uneducated population.

Since 2005, following an uprising sparked by the rape of a female doctor in Dera Bugti district, nationalists have been subjected to enforced disappearances. Sometimes they are released but have been so badly tortured and threatened that they are silenced. However, increasingly, nationalists are being murdered and their bodies dumped in public places, allegedly often by Pakistan’s intelligence agencies.

In 2013 Pakistani novelist and journalist Mohammed Hanif wrote a short, generically-indeterminate book for the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan. He conducted interviews with relatives of the disappeared and wove them into the succinct, hard-hitting stories of The Baloch Who Is Not Missing and Others Who Are. From the father who is overwhelmed by paperwork when his son disappears, to the sister who puts her personal life on hold as she protests for her brother’s release, voices tell of the Kafkaesque bureaucracy and callous authorities these families are up against.

Although Balochistan was a popular setting for colonial writers such as Kipling and Mitford, until recently Baloch were missing from Pakistani literature in English. In the 1970s, Ahmad made the bleak observation that the dead of Balochistan “will live in no songs; no memorials will be raised to them”. This is starting to change. Although the songs are currently being sung by only a few weak voices and the memorials are makeshift and puny, they nonetheless create an impact. An increasing number of writers are turning their attention to this war-torn nation. Perhaps more will join their ranks in the wake of littérateuse Mahmud’s tragic murder.

CLAIRE CHAMBERS teaches global literature at the University of York and is the author of the forthcoming book Britain Through Muslim Eyes: Literary Representations, 1780-1988.

http://www.dawn.com/news/1189376/column-the-baloch-who-is-missing

No comments:

Post a Comment