By Emily Whalen

Best Defense guest columnist

Prime Minister Sharif and his deputies, whether they admit it or not, are worried about Balochistan, Pakistan’s restive western province. Baloch separatists are striking construction projects and police checkpoints with increasing frequency. Law and order seem to have a progressively weaker hold on the region.

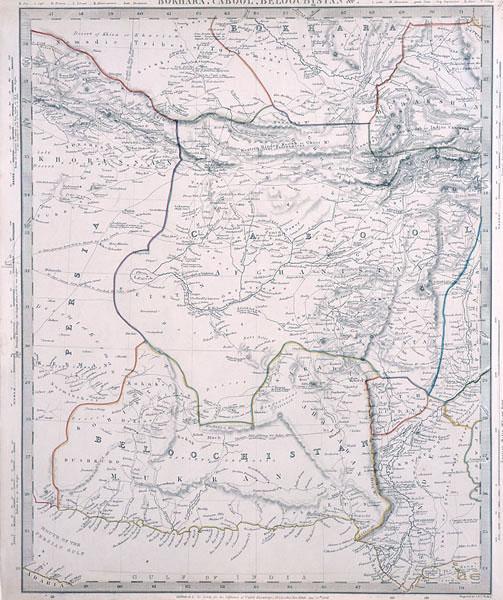

That’s especially significant because Balochistan is rich in resources and covers some of Pakistan’s most strategic geographic regions. It borders Iran, Afghanistan, and the Arabian Sea. The capital city, Quetta, lies along one main transit route to the Khyber Pass and controls other important overland highways. Yet the province remains one of the most undeveloped in Pakistan. Literacy rates in Balochistan fall far below Pakistan’s already dismal 58 percent: As of 2015, just 39 percent of men and 16 percent of women in Balochistan could read and write. Electrical power and water are insecure commodities for the average resident. Balochistan, in the words of Robert Wirsing, is “the area where the struggle for power between the Pakistani state and local tribal elites has been most apparent.”

As with so many of Pakistan’s concerns, conflict in Balochistan stems from the 1947 partition. The princely states that made up Balochistan, particularly the Khanate of Kalat, only hesitantly agreed to partition from India. Once independent, the fledgling Pakistani government faced a formidable Kalat insurgency, a serious strain on the new nation’s already strapped capacities. When parliament ratified revisions to the Pakistani constitution limiting provincial autonomy in 1962, the simmering Baloch separatist movement took up Kalat’s mantle. The Baloch Liberation Army (BLA) — which the European Union and the United States classify as a terrorist organization — and the Baloch Liberation Front (BLF), are the main actors, but separatist sentiment runs deep among many average Balochis.

Throughout 2014, Baloch separatist attacks increased as Baloch separatist leaders disappeared — presumably into ISI interrogation rooms (ISI is the Pakistani intelligence agency). By October of 2014, some 300,000 minorities fled Balochistan to avoid violence targeted against non-Baloch ethnic groups. In February of 2015, Prince Mohyuddin Baloch (prince of the former Kalat state and Baloch tribal chieftain) claimed in an interview with Dawn that the Pakistani government would lose control of Balochistan if it did not work with the Baloch people to find a solution to the conflict. Such a public statement was no doubt directed as much at the Balochi people as it was the Pakistani establishment.

Just under a month before Sharif and Chinese President Xi Jinping announced China’s $46 billion infrastructure investment in Pakistan, five oil tankers belonging to Saindak Metals. went up in flames. The Pakistani army killed five suspected arsonists two days later, Baloch separatists with suspected ties to the BLA. Saindak operates a mine out of Mastung district, one of Balochistan’s most dangerous areas, in cooperation with the China Metallurgical Group Corporation. In May, immediately after Xi’s visit, violent clashes across Balochistan spiked. Most of these events involved attacks on infrastructure and construction projects.

Amounting to nearly 20 percent of Pakistan’s current GDP, the Chinese investment package support projects in energy and transportation, opening the “China-Pakistan Economic Corridor,” to give China overland access to the Indian Ocean. Gwadar, a deep-water port already under Chinese development, will supply China with Arabian Gulf oil once fully operation. The CPEC highway stretches from Gwadar through China’s western Muslim-dominated Xinjiang region — which has its own separatist agitation. CPEC architects originally proposed the 3,000 mile roadway cut directly through Balochistan, but, because of security concerns, rerouted the highway through Punjab, veering into Balochistan at the last possible point, near the coast. Xi isn’t interested in risky overseas investments, and Sharif undoubtedly hopes that a successful CPEC will invigorate Pakistan’s international capital campaign.

Other regional powers are paying close attention to Balochistan. In late 2015, Iranian forces fired mortar shells across the Pakistan border into Balochistan on several occasions, in a display of power meant not only for Pakistan, but also for the substantial Iranian Baloch population. And the Pakistani Taliban (TTP) has ramped up their presence in Balochistan: 2016 has already seen two major suicide attacks in Balochistan linked to the TTP, which claimed 27 lives. Both the Afghan and Pakistani Taliban have close ties with Balochistan; the Afghan’s Taliban leadership cadre, Quetta Shura, found refuge in the region in 2001. The recent increase in TTP activity suggests that years of separatist turbulence have been a sterling advertisement for Balochistan as a haven beyond the reach of the Pakistani government.

Sharif’s response to issues in Balochistan follows a familiar script: blame India. But concrete evidence of Indian support for separatists in Balochistan has never materialized. While it’s tempting to dismiss violence there as status quo, the kind of violence matters as much as its frequency. Pakistan has never been much more than a shaky conglomerate. A seething Balochistan undermines Pakistan’s stability, threatening the balance of power in Central Asia.

Emily Whalen is a doctoral student at the University

of Texas, Austin, specializing in the history of American foreign policy

in the Middle East. She is a consultant for the EastWest Institute and a

former coordinator for ACLED’s Pakistan Team. Follow her on Twitter: @eiwhalen. http://foreignpolicy.com/2016/03/31/balochistan-is-seething-and-that-cant-make-china-happy-about-investing/

No comments:

Post a Comment